|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Alaska's Heritage

CHAPTER 4-3: POPULATION AND SETTLEMENTS

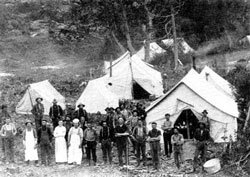

Alaskans live near lines of transportation and resources At the time of the purchase in 1867, an estimated 2,000 people lived within Alaska's borders. By 1910, nearly 65,000 people resided in Alaska. Forty years later, 128,643 people lived in Alaska. In 1984, an estimated 572,000 people lived in the state. Throughout Alaska's history, the people have generally lived near lines of transportation. The early settlements were close to the ocean or along the major rivers. Later, communities were established adjacent to railroads and roads, and still later, to airfields. The other choice for the location of settlements was access to resources, such as minerals or fish, that could be economically developed. Americans occupy Russian posts and towns Many of the Russians in Alaska chose to leave in 1867, yet the number of people in Alaska stayed about the same. American traders, government representatives, and speculators replaced the Russians who left. The functions of most of the Russian settlements also did not change greatly. Americans occupied former Russian fur trading posts at St. Michael, Unalaska, and the Pribilof Islands in the west, at Kenai and Kodiak in Southcentral Alaska, and at Sitka in Southeast Alaska. A few new settlements are created before 1897  Around roadhouses, that were built along Alaska's roads and trails, miners and trappers frequently congregated when not working their claims or traplines. Post offices and telegraph stations were often located adjacent to roadhouses as well. Collection Name: Alaska Historical Library, Skinner Collection. Identifier: PCA 44-6-13 Several cannery sites around Alaska grew into small villages. Among them were Karluk on Kodiak Island and Homer on the Kenai Peninsula. In Northwest Alaska, whalers and traders established shore-based whaling stations. Around the stations Eskimos gradually congregated. Mining camps become new communities The discovery of gold in the Canadian Klondike in 1896 lured large numbers of people to Alaska. Between 1890 and 1900, the total population of Alaska nearly doubled, to about 63,000 people. Few of the people who came seeking gold intended to stay. Very few found the gold they sought. Less than one out of every 100 men and women who journeyed to the gold fields went away rich. The people, however, aided in the development of Alaska. Towns such as Nome and Fairbanks would not exist without their golden past. Supply camps near the gold fields and along the routes to the mining areas were established. Many, such as Dyea, were short-lived towns. A few, such as Skagway and Valdez, survived. Circle City, founded in 1694 on the south bank of the Yukon River, near birch Creek where gold was found, was a typical gold rush boom town. Almost all of the buildings were log structures. The town stretched along the river. There were two principal streets. Some residents called their log cabin community the "Paris of Alaska." To others, Circle City was a dirty, ugly, frontier town. When Episcopal Bishop Peter Trimble Rowe visited Circle City in 1895, he described it as "a row of saloons, gambling houses and dance halls, and general stores." The town survived when miners left. It became the base for a number of trappers. 8y the summer of 1900, more than 20,000 people were in a new mining camp, Nome, on the Seward Peninsula. It had 50 saloons. Shootouts and brawls were common. Perhaps one in every ten persons was a woman. Some women worked with their husbands. Others had their own businesses, cooked in roadhouses, or ran boarding houses. Some of the mining and supply centers survived as collecting and distribution centers. After the initial rush, churches, schools, and public buildings were built. Tents and other temporary quarters were replaced with more permanent buildings of log and frame construction. Several company towns flourish in Alaska In several mining areas, large corporate mining operations moved in after the initial stampedes. They brought in hydraulic mining equipment, dredges, or built stamp mills to mine hard-rock gold. The companies at the Treadwell gold mines at Douglas, at the Kennecott copper mines, at the Chatanika gold fields, at the Independence gold mines, and at the Goodnews Bay platinum mines, developed "company towns." The company owned the land and constructed boarding houses, mining offices, and other necessary community buildings.  The town of Nome on the Seward Peninsula was founded in 1900 when gold was discovered in the gravels of Anvil creek. During the period 1897-1907 more than 50 gold rush towns existed around Alaska. Most were abandoned and little evidence remains of them. Collection Name: Alaska Historical Library, B.B. Dobbs Collection Identifier: PCA 12-72 During the 1910s, the U.S. Navy sponsored a thriving community in the Talkeetna Mountains, 74 miles from Anchorage. The town of Chickaloon had homes, a schoolhouse, stores, a power plant, dormitories, a mess hall, and most important of all, deposits of coal. The navy developed the coal mine to produce fuel for its ships. Like so many other Alaska mining towns, Chickaloon grew quickly and almost as quickly declined. The navy began to convert its ship engines to burn oil instead of coal. Not long after, the navy ordered the Chickaloon mine shut down. Almost overnight, most of the people left the town. Although seasonal, many canneries were essentially company towns. The owners transported their workers to the cannery in the spring and returned them to their home base in the fall. At the cannery, the owners provided workers food, lodging, and some recreational facilities. At each company town, in Alaska, when the owners discontinued mining or canning operations, the town was abandoned. Settlements thrive around military posts The army stationed at Sitka from 1867 to 1877 contributed significantly to the economy of the community. This was true at later dates and in other Alaskan communities as well. During the frenzied gold rush years, seven army posts were established around Alaska. The posts were complete communities by themselves. They had quarters for the personnel, mess halls, stables, a laundry, blacksmith shop, machine shop, hospital, and warehouses. Streets were often laid out as well. The communities adjacent to the posts often grew. They provided additional goods and services. When most of the army posts around Alaska closed in the 1920s, the economies of nearby local communities faltered. The same scenario occurred during and after world war II. The communities near military posts in 1984 recognized the significance of the bases and their personnel to their local economy. When closing severe! bases in Alaska was suggested in 1984, community residents actively campaigned to keep the bases open. A number of Alaska communities exist as transportation and communication centers New Alaskan communities were founded after 1900 when roads, railroads, and the Washington-Alaska Military Cable and Telegraph System were constructed. Among them were Seward and Cordova.  Although company towns provided recreational facilities and many other amenities, communities nearby often flourished as well. This is McCarthy's camp that was four and a half miles from Kennecott. Many workers hiked to McCarthy to go to the saloons. Collection Name: Alaska Historical Library, E.A. Hegg Collection. Identifier: PCA 124-16 Along the route of the Alaska Railroad, built between 1915 and 1923, a number of communities grew. The railroad encouraged new towns by surveying and platting sites and auctioning lots. Anchorage, Alaska's largest city today, began as a railroad construction camp of the Alaska Engineering Commission. In 1915, word spread around Alaska that the commission would be hiring workers at a camp at the, mouth of Ship Creek. Several hundred people set up tents at the site. The Alaska Engineering Commission surveyed a town-site and held an auction to sell lots. The camp was renamed Anchorage. A few years later, the Alaska Engineering Commission moved its administrative headquarters from Seward to Anchorage. This move gave the new community a stable economic base. Because the Alaska Engineering Commission contracted with independent firms to build and maintain sections of the railroad, many contractors moved to Anchorage. The contractors needed laborers, and this encouraged more people to locate at Anchorage. The railroad also aided the economic fortunes of several established communities along its route. Nenana, an Athabaskan community, became a hub of activity. There the railroad crossed the Tanana River. For many years the railroad operated a fleet of steamboats that home ported at Nenana and served communities along the Tanana and Yukon rivers. Jobs with the railroad or at the docks were available. Consequently, many people moved to the town. A few towns in Southcentral and Interior Alaska, such as Knik and Hope, declined when the railroad bypassed them. Alaska Natives are cool to reservations The U.S. Government attempted to provide land for Alaska Natives in the same way it had for Indians in the Western United States. That way was to establish reservations. But Alaska was different. There was plenty of land available and few people interested in it. When the Alaska Railroad was built, the government expected that there would be a substantial increase in people and use of the land in Interior Alaska. To prevent the misunderstandings and often violent conflicts that had characterized Indian/nonNative relations in the west, government officials met with Alaska Native leaders, such as the Tanana chiefs in 1915. Some Alaska Native groups rejected proposals for reservations. The reservation system was not widely implemented in Alaska, although some were created. Over the next 30 years, three reservations in Interior Alaska were established. A withdrawal at Fort Yukon totaled 75 acres. The Venetie-Chandalar reservation included almost 1.5 million acres and encompassed four villages. The Tetlin reserve in the Fortymile River area covered 786,000 acres. Reservations at Noorvik, Point Hope, Wales, and Diomede in Western Alaska were created. In 1960, however, only 183 Interior Alaska Natives lived within reservations. One reservation in Alaska is particularly unique. When William Duncan, a Church of England missionary, was denounced by Canadian church leaders in the 1880s, he and his followers appealed to the U.S. Government for a site to live. As a result, Congress created a reservation on Annette Island in Southeast Alaska. Duncan and his Tsimshian parishioners moved there in 1887. Although most Alaska Natives did not live on reservations, many lived in rural communities that were predominantly Native. When the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act was passed in 1971, village corporations were created. Creating these units was intended to help the over 160 villages survive. The population of Alaska stabilizes then booms again Most Alaskans lived in communities, although some might be quite small. One reason was that living alone in an isolated area was challenging and dangerous. Another was that people sought the company of others. By 1910, the excitement of the gold rush was over. Although the population declined, more people lived in Alaska than had prior to 1896. People could find work at mining camps, at canneries, or on public construction projects. When the United States entered World War I, Alaska's population further declined. A greater proportion of Alaskans entered the armed forces than did residents of any of the states. Alaska's population did not significantly increase again until after the military built a number of posts around the territory during World War II. Major naval stations were constructed at Sitka, Kodiak, and Unalaska. Army posts were built at Fairbanks and Anchorage. Air fields were constructed at a number of sites around the territory such as Galena, Gulkana, and Yakutat. The new Glenn Highway connected Anchorage with the Richardson Highway. The Alaska-Canada Highway was opened after the war. Thousands of soldiers and construction workers had come to Alaska during the war years. Many decided to make Alaska their home at the end of the hostilities. Between 1940 and 1950, the territory's civilian population increased from roughly 74,000 to 112,000. This influx put a tremendous strain on Alaska's already inadequate social services, such as schools, hospitals, housing, and local governments. Many of those who moved to Alaska after 1945 were attracted by Alaska's remote areas. Upon their arrival, however, most of the migrants settled in the larger communities that offered employment and the goods, services, and cultural elements found in the places they had left. Simultaneously, these same attractions were luring rural Alaskans to the cities. Disasters plague many communities Natural disasters have severely damaged and destroyed a number of Alaska communities over the years. The Mount Katmai eruption in 1912 buried several Native villages in the area. Spring flooding during the breakup of river ice has harmed Bethel and Fairbanks, each on more than one occasion. Storms have sent sea water across Nome's beaches and flooded the town. Some villages in the Yukon-Kuskokwim delta and the Yukon Flats areas have relocated to higher ground as water has encroached on their communities. To date, the earthquake that shook Southcentral Alaska on March 27, 1964 caused the greatest damage to Alaska. A number of communities, such as Chenega in Prince William Sound, were destroyed. The city of Valdez had to be relocated. Ports at Seward, Whittler, and Anchorage were damaged. In addition to natural disasters, accidents such as fire have damaged or destroyed communities. Much of Nome's business district was destroyed by fire in 1900, and again in 1905 and 1934. The community was largely one of frame structures built on lots only 20 feet wide. Seward, in Southcentral Alaska, survived two large fires in its business district. Oil development almost doubles Alaska's population Alaskans had hardly accommodated the post-World War II immigrants when oil discoveries were made in Cook Inlet and at Prudhoe Bay. During the 1970s, the population of Alaska nearly doubled. Literally thousands of people came to Alaska during construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline in the 1970s. The rapid increase caused severe problems in towns that serviced the project. There were not enough facilities to handle the hordes of people. In Fairbanks, housing costs soared. In Barrow, more people found employment. In Anchorage, the population doubled to 200,000 within a few years. The city emerged as the focal point for Alaska's financial and business interests. Crime increased in towns throughout the state. Suburban areas develop adjacent to the major towns During the 1970s, less-crowded areas connected by roads to Alaska's major cities began to attract people. Land prices were usually more reasonable. The Matanuska Valley, 40 miles from Anchorage, and Eagle River, 11 miles from Anchorage, were two such suburban areas. Auke Bay, 13 miles from Juneau, was another. North Pole and Ester outside of Fairbanks grew. Alaska's population continues to grow rapidly In 1980, 64,103 Natives lived in the state. Of this total, 34,144 were Eskimos, 21,869 were Indians, and 8,090 were Aleuts. Although it is the largest state in area, Alaska had the smallest population of the 50 states in 1984. Then, 572,000 people lived in Alaska. At the same time, Alaska had the nation's fastest growing population. Its population had increased 19.2 percent over three years.

|

|||||||||||||||||

|