|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Alaska's Heritage

CHAPTER 4-4: FOOD, CLOTHING, AND SHELTER

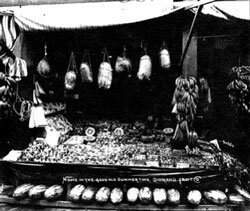

Americans encounter difficulties getting food Americans in Alaska during the late 1800s confronted the same problems that the Russians had in obtaining food they wanted and were accustomed to eating. Supply ships did not arrive regularly. Attempts to plant grains or raise stock animals were unsuccessful. Attempts to raise root vegetables such as potatoes, turnips, and carrots were moderately successful, but not many people bothered to plant gardens. A few people kept dairy cows. As had the Russians, the Americans relied on locally-available game animals including moose, caribou, and deer. They also ate birds and waterfowl. When reindeer herds were established in Western Alaska, fresh reindeer meat could be obtained. Otherwise, Americans ate canned or salted meats. The Americans also ate fish, chiefly salmon, but halibut, grayling, and cod as well. Although some non-Natives lived off the land, most imported a lot of their food. Canned goods, when they became available in the late 1800s, were popular. Prior to that time, most food supplies were shipped to Alaska in barrels. Flour, sugar, molasses, rice, and beans were the most common imports. Fruits and vegetables were dried. Much salted meat, usually ham or bacon, was also imported. At Sitka, the major American community in Alaska during the 1870s, many non-Natives purchased fresh meat and fish from the local Natives instead of fishing or hunting themselves. Sitka's temperate climate made it impossible to preserve food by freezing as was possible in Northern Alaska for at least nine months a year. Fortunately, a ship arrived more or less regularly each month with food supplies. Other communities around Alaska were not served so well. Few companies engaged in transporting supplies to Alaska before the Klondike gold rush. Shipping in Alaska's largely uncharted waters was risky. There were few people at most communities. Because of the great distances, shipping charges were high. Most people bought only basic foods. When the annual supply ship did not arrive, however, shortages occurred. After the Alaska Commercial Company received its exclusive lease to fur sealing on the Pribilof Islands in 1870, it sent a supply ship to Western Alaska each year. The ship stopped at Unalaska and Atka in the Aleutian Islands, at Nushagak, at the mouth of the Kuskokwim River, at St. Michael, and at St: Paul and St. George in the Pribilof Islands. Traders and missionaries traveled from their posts to these locations for their supplies. Then the year's supplies, and perhaps trading goods as well, had to be transported upriver or overland. The Native people begin to depend on non-Native foods While Americans in Alaska adopted Native foods, the Natives began to use more non-Native foods. Natives who lived near trading posts were encouraged to trap fur-bearing animals and to sell them to the trader. This meant that they spent more time obtaining furs, and less time gathering food. The furs most valued by the traders were from animals which the Native people usually did not eat, such as beaver. The introduction of firearms changed Native social patterns. Individuals could operate independently. In Northwest Alaska, for example, the last large, cooperative corralling of caribou took place in 1906. Instead of a community-wide effort, a family had to hunt or gather and preserve its food. In the late 1800s and through the 1900s, whaling companies or traders in the Arctic "bought" an Eskimo crew in the fall for the next spring's hunt. Payment was in goods. Each crew member might receive 400 pounds of flour, 10 cans of molasses, coffee, tea, tobacco, matches, and calico. If the crew killed a whale, they might receive a bonus, additional food or a rifle, lead, powder, and primer. Food supplies become more available following the gold rush The large numbers of people who rushed to Alaska after the gold discoveries in the late 1890s meant that more supplies were needed. A number of companies organized to bring and to sell supplies in the mining communities and along the routes traveled to get to the gold fields. Freight costs were added to the prices of food. Competition was limited. In many areas, the prices for food were outrageous. In 1903, at Council City on the Seward Peninsula, flour sold for $15 a barrel and bacon for $.40 a pound. Butter, milk, and eggs were scarce. Even the supply of canned goods was limited. Still, more food and a greater diversity of foods became available during this period.  The Diomand Fruit Company's outdoor stand at Nome. During the gold rush heydays, a great variety of enterprises could be found in the boom towns. Collection Name: Alaska Historical Library, B.B. Dobbs Collection. Identifier: PCA 12-63 Because there were few roads, virtually all supplies were distributed to trading posts and mining camps by coastal trading vessels and riverboats that operated along the major rivers. Except in Southeast Alaska, the rivers froze during the winter. Ice in the Bering Sea and Arctic ocean prevented ships from bringing supplies to these areas for nine months of the year. People had to obtain a year's supplies during the summer. Before iceboxes and refrigerators were in general use, Alaskans in areas where there was no permafrost stored food in root cellars. In permafrost-affected areas, the residents built caches. By the 1920s, Fairbanks and the other communities along the Alaska Railroad and Richardson Highway were getting supplies more frequently. The introduction of refrigeration also meant fresher food. People in most northern and western Alaska communities, however, had to wait until air transportation became available in the late 1940s and 1950s. High freight charges continued to make fresh foods luxury items for most Alaskans. Although more and a greater variety of foods became available to Alaskans during the early 1900s, they still did not have the variety of foods available in the 1980s. It was not unusual for a family to purchase a side of beef or a bushel barrel of potatoes. Evaporated or powdered foods, such as milk or eggs, were bought in quantity. Eggs could be bought by the case. They were expensive because they required special handling. Although they could be eaten, old eggs were rubbery in texture. Rural Alaskans continue to order food supplies outside of their communities Air transportation costs declined during the 1970s and 1980s. More people lived in Alaska which meant greater amounts of food products were needed. Costs could be lower per unit item. Food prices declined and variety improved. Food products in rural Alaska still were costly. Many rural residents continued to buy bulk orders of groceries from stores at Anchorage or Fairbanks. They found that paying shipping costs was more economical than buying food locally. A gallon of milk that cost $5.69 at Barrow could be purchased in Anchorage for $1.99. Pilot bread, evaporated milk, coffee, paper towels, cereals, canned foods, shortening, sugar, and flour were frequently ordered items.Convenience foods begin to replace traditional foods Fresh meat was one of the most expensive food items in Alaska. The costs to hunt, trap, and fish for fresh meat continued to increase. Equipment costs, license fees, and butchering fees increased. Because the costs to bring fresh meat from outside Alaska declined, many local producers went out of business. Studies to compare the nutritional values of traditional and imported convenience foods were conducted. Traditional foods, moose and salmon particularly, were richer in protein and fats. Foods that have replaced them were rich in carbohydrates. Cereal was more frequently eaten for breakfast. Desserts were added to meals. Foods with artificial preservatives and ingredients appealed to many, however. Natives adopt Euroamerican clothing One of the major trade items in Alaska was cotton cloth. Increasingly, Alaska Natives used cotton for summer parkas. One reason for this was that the furs they had formerly used could be sold for money, food, or other items. Cotton and wool garments were more comfortable to wear. The fabric was easier to sew. It was more colorful. Skin clothing continued t0 be made and worn by Alaska Natives. During the 1940s, the Skin Sewers Cooperative formed at Nome. Eskimo women made skin parkas, pants, hats, and mukluks for many of the military service personnel in Alaska. Non-Natives adopt Native clothing As had the Russians, the early American fur traders living at isolated locations frequently adopted Native clothing styles. In the few communities, people wore clothing styles of the period. Although interested in fashion, most Alaskans were more concerned with warmth.  The dry goods (fabric and sewing notions) department at the Alaska Mercantile Company store at Nome in 1907. Ready-made clothing was just beginning to become available in the early 1900's. Collection Name: Alaska Historical Library, B.B. Dobbs Collection. Identifier: PCA 12-104 Alaskans delight in mail-order catalogs After the inauguration of parcel mail service in the early 1900s, many people in Alaska began to order clothing from catalogs such as Sears, Roebuck and Company. Ready-made clothing increasingly replaced hand-made clothing. When this happened, clothing stores opened in the larger Alaskan communities. A few nation-wide department and catalog order businesses opened stores in Alaska after World War II. J.C. Penney, Montgomery Ward, and Sears, Roebuck were among them. The Northern Commercial Company was one of Alaska's first independent department stores. Still, in 1984 Alaska lacked the numbers of people required to attract many of the large national department stores. Americans initially adapt to Native housing The early American trappers, traders, and prospectors in isolated areas of Alaska did what the Russians had done. Many adopted Native housing styles. Others constructed log cabins. The non-Natives introduced some innovations to the Native houses. In the Aleutian Islands, for example, the introduction of glass windows and doors changed the location of the entryway to a barabara. One entered through the side of the barabara, not, as before, through an opening in the top. Windows allowed light to enter these semi-subterranean dwellings and made it easier for heat to escape. Missionaries instigate canes in Native housing Many of the missionaries to Alaska felt that the Native people should abandon their communal homes and live in single-family homes. They also felt the semi-subterranean homes of the Native peoples in Western Alaska were not sanitary. Frame houses were introduced. In the Pribilof Islands, the Alaska Commercial Company shipped California lumber to the islands and built frame houses for the people. At Unalaska, competing trading companies offered frame houses to families in exchange for an agreement to hunt or to fish exclusively with that company. The frame houses were not always well received. Many people could not afford to heat the houses. The houses were frequently poorly insulated. Over the years, however, the single-family frame houses replaced the traditional Native structures. Alaskan architecture is practical Although a wide variety of forces affected Alaskan architecture, it was always pragmatic. Initially, buildings were hastily constructed in response to an immediate need for shelter. At mining camps, buildings were erected to get a business underway or to provide cover before the cold, long winter arrived. Single room log cabins, often only 14 by 20 feet, were common. Commercial structures were single story buildings. The more elaborate had false fronts. Buildings were limited by the availability of materials and the machinery available. Many of the people who came to Alaska seeking gold did not plan to stay indefinitely. They planned to make their fortunes and depart. Community planning was largely unknown. In many mining camps or around trading posts, no attempt was made to organize a community. Each mining camp had its camp followers. Saloon keepers, gamblers, cooks and bakers, bankers, lawyers, newspaper publishers, and doctors descended on the new towns. Most people in these towns lived in small log cabins heated by wood stoves. The ground was covered with layers of newspapers topped with canvas. Southeast Alaska leads the way in architectural development in Alaska As some of the early mining camps such as Juneau and fishing communities such as Ketchikan took on an air of permanence, new buildings were built to last for a number of years instead of merely meeting an immediate need for shelter. Buildings in the towns included homes, churches, schools, social lodges, and businesses. Oil stoves, steam heat, electric lights, and plumbing were added. The new houses were built better. Many had painted wood siding or shingles. Sheet metal or shingles replaced sod roofs. Technological advances during the 1800s had a major impact on the building industry world-wide. Alaska benefited as well. Power equipment was one innovation. Building embellishments such as curved bannisters, turrets, and non-rectangular windows could be mass produced. Standardization helped lower costs dramatically for such detailing. Buildings became more ornate. Pattern books, trade catalogs, builders handbooks, and building magazines advertising new trends were published. Alaska residents could purchase plans to have a house or a storefront similar to ones the had admired in Seattle, New York, or in a magazine. Mass produced furniture could be purchased. Dry goods catalogs offered "sets" for sale that included a room's furniture, curtains, and all accessories. Still, Alaskans had to adapt their buildings to their environment. At Ketchikan, many buildings had to be set on pilings. At Juneau, a number of structures had to be built on the steep mountainside. At Nome, buildings were constructed on top of permafrost. In Southcentral Alaska, roofs with a low pitch were common to reduce the volume of space inside to be heated. To trap cold air, enclosed entryways became a standard feature of homes in the North. During the early 1900s, a number of new towns in Southcentral and Interior Alaska were founded. Cordova, Seward, and Fairbanks were among them. A law passed in 1900 gave these towns advantages earlier communities had lacked. The new law provided for incorporation of towns with a population of 300 or more. It also authorized city councils and school boards and allowed local governments to keep 50 per cent of the territorial license fees collected within the city limits. The money could be used to help pay the cost of running the new towns. Regulations could be adopted to establish minimum standards of construction for the safety of the public at large. In 1915, the railroad town of Anchorage was founded. The dominant architectural style in these post-1900s communities was cottage architecture. Businesses and houses were of frame construction, simplistic as opposed to ornate, and essentially utilitarian. Because of the high costs of building materials, it became common around Alaska t0 move structures. The buildings reflected the boom-or-bust experiences of many Alaskan communities. Buildings from Knik were moved when the railroad by-passed the town to Wasilla and Matanuska. Buildings from Chickaloon were moved to Wasilla and Anchorage during the 1920s after the coal mines shut down. Public buildings are to be functional As the federal government began to provide more services around Alaska, it constructed buildings. The most common public buildings were schools, post offices, and telegraph stations. These buildings were to serve specific functions and were not intended to be frivolous or innovative. At the time, each federal agency had architects on its staff who designed their buildings. Although they usually worked from standard plans, most architects included design elements to reflect the local area and included decorative extras such as murals. Among the public structures built was a federal and territorial building at Juneau. It was built in 1930. The building had four exterior columns of marble from the Tokeen marble quarry in Southeast Alaska. Marble was also used for interior walls and trim. When Alaska became a state, the building became the state capitol. Another public building constructed at Juneau around the same time was a house for the governor. During the 1930s, several Alaskan communities benefited from the federal Public Works Administration's building program. In Anchorage, Fairbanks, and Sitka new federal buildings were built. Incorporated cities built structures. Many constructed schools, some built libraries. The City of Anchorage constructed a large city hall during the 1930s. A number of structures that are considered to be public buildings, such as churches or social halls, were built by private groups. A major construction boom follows World War II After World War II ended in 1945, Alaska experienced a population boom. The years of depression and war were over. The expansion of military activity in the territory and the discovery of Alaska by many individuals who had been stationed around Alaska during the war attracted people. Buildings to house the people and provide necessary services were needed quickly. Standardization in construction styles of homes and buildings resulted. The first subdivisions around Alaska's major cities appeared. New technological advances allowed for new developments in Alaskan architecture. Steel 1-beams, escalators, and elevators meant that high-rise buildings could be built. Most of the commercial buildings, however, were metal panel functional structures. During the 1970s, more elaborate architectural buildings, usually private homes, began to be built in Alaska's larger communities. In 1980, the State of Alaska started two programs to assist individuals purchasing homes. The programs were administered by the Alaska Housing Finance Corporation and the Department of Community and Regional Affairs. By 1984, one-third of the homeowners in the state, approximately 25,000 people, had received mortgage subsidies through these programs. The subsidies ranged from $2,700 to $3,600 per year for the life of the mortgage. Between 1980 and 1983, the cost to the state for these programs was over 1.2 billion dollars, $450 million of which would not be repaid to the state. Another housing program, the Federal Indian Housing Program, provided over 4,000 homes in rural Alaska between 1975 and 1984.The mid-1980s also saw, as interest increased in energy conservation, experiments in building modern houses that were partially underground, thus drawing from traditional Native techniques and bringing architectural development in Alaska full circle.

|

|||||||||||||||||

|