Geography

Places

Place to a geographer is somewhere that people can identify as special or distinctive. “My house,” “my community,” “my state,” or “my country,” are all examples of geographic areas that have been given special meaning by people. We have all heard the phrase: “There is no place like home.” We may or may not agree with the statement. However, it does tell us that home is a place that has intangible characteristics that convey special meaning.

Places, to geographers also have tangible physical and human geographic characteristics. Physical characteristics would include landforms, climate, hydrology, vegetation, and animal life. Human characteristics would include buildings, stores, offices, communications systems, and transportation systems and so on. Of course, these places change with time. Anchorage and Dillingham are certainly not the same places that existed in those locations 50 years ago.

In Alaska, the terms “urban” and “rural” are used to distinguish two different areas of the state. A recent Commonwealth North study noted that urban and rural were difficult to define. In fact, the study found many definitions of urban and rural. To help clarify the differences Commonwealth North offered a perspective for each that conveys a qualitative sense of place. The urban element represents “…a cash economy, formalized government structure, ready access to public services, competitive individualism, and an increasingly multicultural non-Native heritage.” In contrast, the “rural” element represents a subsistence economy, informal traditional governance, inadequate access to public services, communal decision-making and a substantial Native heritage.”

We also give names to places, such as Alaska, or Anchorage, or Tok. Place names often hold considerable meaning. To Alaska’s Native population, place names tell much about the nature of a place, such as special environmental or historical characteristics. (Shem Pete) Sometimes place names are controversial. The controversy might relate to the correct spelling of a name. In one case, the controversy has continued for years--the “right” name of the tallest mountain in North America. Today, the Alaska Historical Commission reviews names proposed for physical features in the state. The commission then sends its recommendations to the U.S. Board on Geographic Names for final approval.Regions

For geographers, the region is a conceptual tool that provides a way to organize space. If that concept seems like something that would not cause controversy, think again. After every decennial census in the United States, each of the fifty states has to redraw its electoral districts since districts change in population size and composition over time. Electoral districts are an example of what geographers call regions. How they are drawn can have a major effect on which political party might get more or less votes and which candidates might find their districts dramatically changed or eliminated.

A boundary line encompassing Gwitch’in speaking communities represents a language region. Similarly, the area of tundra vegetation in Alaska can also be a region as can the area that identifies which students will attend a particular school. Regions, then, can be of any size, local to worldwide, and they can be defined by one or more features or criteria.

Types of Regions

Geographers use three major types of regions in their work: formal, functional, and perceptual. Let’s look at each one of these regional types in the context of Alaska.

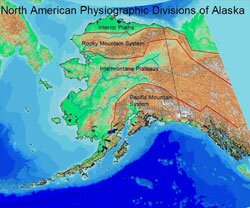

Figure PS.1 - Physiographic Regions

Collection Name: Pearson, Roger and Marjorie Hermans. (Eds.) 2001. Alaska in Maps. Anchorage: Alaska Geographic Alliance, Map 11.

Regions can be overlapping and as such, can provide complexity where we might not expect it. Consider the case of Fort Yukon. It is a predominantly Athabascan community of 600 people. Certainly it is a small community by U.S. standards. Yet, Fort Yukon is part of 18 different political and service regions. More generally, we find throughout Alaska federal and state agency regions ranging from Rural Education Attendance Areas and boroughs to U.S. Post Office regions and Alaska Fish and Game management regions. These regional boundaries often crisscross each other—and properly so. After all, each of these regions serves a specific purpose.

Functional Regions.People, goods, services, and information move between places. The geographic pattern formed by these movements constitutes a region based around a central node such as a city. Geographers refer to the area formed by these movements as functional regions.

Airline flights operate out of hubs and fly from major hubs to smaller hubs. For Alaska, the major hub outside of the state is Seattle. More direct flights from Alaska go to Seattle than to any other city outside of Alaska. This is not surprising given Seattle’s location and its historic economic ties to territorial Alaska.

Within Alaska, Anchorage has become the major hub with direct flights to important communities throughout the state. As the largest community in Alaska, Anchorage also acts as a major service center for commercial, financial, and government activities throughout much of the state. The Alaska Supreme Court is based in Anchorage. Within Southeast Alaska, Juneau is the major airline hub. This function is enhanced by Juneau’s role as Alaska’s capital. Fairbanks, Barrow, Kotzebue, Nome, and Dillingham are other examples of more local airline hubs. Airline schedules are a good indicator of regional hub activities of a community.

Another example of functional regions is found in daily commuting patterns in the Anchorage area. While the Anchorage Borough defines a political (formal) region, it does not reflect the daily traffic patterns. Many people who live in nearby Wasilla and Palmer and surrounding areas commute daily to work in Anchorage. While they live in the Matanuska-Susitna Borough, they are part of the Anchorage functional region. Like formal regions, functional regions change over time. During the 1930’s, Anchorage was not the dominant center of the territory. Fairbanks, with its mining activities, railroad terminal, and airline services was the major nodal center for northern and western Alaska. Perceptual Regions.Not all regions can be neatly defined by specific criteria. Where, for example is the “South” in the U.S.? Should it be defined by state boundaries? Should we consider the South just the states that were part of the Confederacy? What about dialect? Where exactly does one find the southern “drawl”? Should Florida be considered part of the “South”? Despite all of these questions the fact is that we all recognize a general area called the South. It has regional characteristics such as a dialect, a distinctive climate, a shared history, and so on. This type of region is usually based on a number of general criteria and the exact boundaries are not sharply defined. Geographers call these perceptual regions.Alaska, as we have seen, has a number of formal regions and functional regions. Yet, most Alaskans also recognize certain perceptual regions. We don’t all agree on the exact number and boundaries of these regions. Some confusion naturally results from this situation. To clarify the situation, let’s look at the regional system used by the Alaska Virtual Library and Digital Archives (Figure PR.4.).

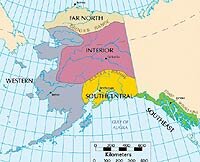

The scheme has five regions, Far North, Western, Interior, Southcentral, and Southeast.

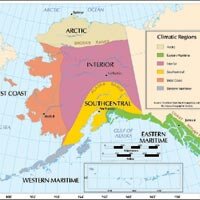

There is no one criterion that defines these regions. However, we can see how the regions do closely correlate with other geographic features. For example, there is a general relationship between the five perceptual regions and the six climatic regions, especially if we combine the West Coast and Western Maritime climatic regions. (Compare Figures PR.4. and PS.3.)

The best spatial correlation, however, is with traditional Native language boundaries. If one simplifies the Native Language boundaries to four groups: Inupiaq, Yup’iq and Alutiiq, Athabascan, and Tlingit-Haida-Tsimshiam-Eyak (Figure G.7) the spatial match is fairly close. However, Southcentral Alaska has an overlap of linguistic groups.

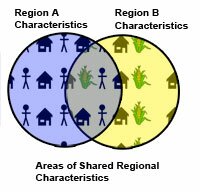

A Venn solution. One way to think of perceptual regions is to consider each of the regions as having a distinctive set of core traits, such as certain climate, vegetation, resource base, traditional language group, and so on. The outer limits of the region will probably mingle characteristics with a neighboring region with different characteristics. The blending zone would match the overlap of the Venn diagram as shown in Figure PR.5.