|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Alaska's Heritage

CHAPTER 4-10: ROAD TRANSPORTATION

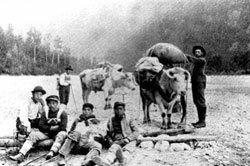

Early Alaskans did not need improved roads Native Alaskans had an extensive system of overland trade trails in use before the first Euroamericans arrived in Alaska. When the Euroamericans came to Alaska they made use of the Native trails, but did little to create new ones. From 1741 to 1867, the Russians in Alaska built almost no new trails or roads. Relying on water transportation in summer and sled transportation in winter to move their cargoes of furs, supplies, and fur traders, they really had no need to build an extensive overland transportation system. The Americans who came to Alaska immediately after the Russians, in 1867, also had no need of elaborate roads and trails. In Interior Alaska they continued the fur trading begun by the Russians and had similar requirements for freight and passenger movement. In Southeast Alaska, where the Americans did begin to mine gold and silver (at Sitka in the 1870s and Juneau in the 1880s) and thus needed better transportation, the mines were adjacent to water transportation. New trails are needed in 1890s  The Indian packers in this 1897 photograph are shown on their return from the summit of the Chilkoot Trail. They each made $18 for a day's work of packing miners' supplies up the trail. The oxen were regarded as the most desirable of pack animals for su Collection Name: Alaska Historical Library, F. LaRoche Collection. Identifier: PCA 130-12 As the number of prospectors and miners working on the upper reaches of the Yukon River increased, more and more supplies were needed. River traffic on the Yukon increased to meet this need, but some entrepreneurs looked to improved overland transportation as a way to get supplies to the prospectors and miners. One such person was Jack Dalton. In the 1890s, he bargained with the Chilkat Indians, whose traditional territory was in the vicinity of present-day Haines, to use their trade trail which ran from Lynn Canal up the Chilkat River, over the mountains, and into the Yukon River drainage. When the bargain was agreed upon, Dalton had permission to use the Chilkats' trail. He cleared the-trail, and bridged swamps and streams. Operating the improved trail as a toll road, Dalton charged $2 per cow and $2.50 per horse. In 1898, the U.S. Army sent explorers to Alaska to look for potential overland routes from ice-free ports to the Yukon River. One group investigated the Susitna River valley, another group investigated the Matanuska River valley, and a third group investigated the Copper River valley. These explorers recommended military road construction to tie various mining camps together. The officer in charge of the first two groups concluded that while a railroad might later be built up the Matanuska valley to Interior Alaska, at the time such a project was premature. The officer in charge of the third group recommended that a military trail should be built north from Valdez, on Prince William Sound, to Eagle, on the Yukon River. The army builds Alaska's first long road The following year, construction of the Valdez to Eagle trail began. Axe-wielders followed survey crews. A third party with picks, shovels, crowbars, and dynamite followed to grade the trail cleared with axe work. Sledge hammer crews followed the graders, clearing debris left after blasting. The first year, 93 miles of pack horse trail were constructed north from Valdez. The resulting trail was only five feet wide in places, but it made overland travel to Interior Alaska much easier than it had been. In 1903, a Senate "Committee On Territories Appointed t0 Investigate Conditions in Alaska" looked at Alaska transportation problems. At the beginning of 1904 the committee recommended that the federal government build a system of transportation routes in Alaska. That year, Congress authorized a survey so that the Valdez-Eagle trail could be upgraded to a wagon road. The survey was completed the following year. At this tire there were less than a dozen miles of wagon road in all of Alaska. In 1904, Congress authorized 70 per cent of funds collected from licenses issued outside of towns in Alaska to be used by the War department to build roads and trails in Alaska. At the same tire, each able-bodied male in Alaska living outside incorporated towns was to give two days labor or eight dollars cash toward road-building each year. A Board of Road Commissioners was established to oversee construction and maintenance of roads and trails. It consisted of three army officers appointed by the Secretary of War. Between 1905 and 1906, the hoard of Road Commissioners flagged 247 miles of winter trails on the Seward Peninsula. This placed red flags 50 to 150 feet apart along the trails to make winter travel less hazardous. The Road Commissioners also built 40 miles of improved roads, upgraded 200 miles of existing trails, and cut 285 miles of new trails. By 1911, the road-building organization, now known as the Alaska Road Commission, had flagged several hundred miles of winter trails, built 576 mites of pack trails, 507 miles of winter sled roads, and 759 miles of wagon roads. More than half the wagon road mileage, however, was on one route-the Valdez to Fairbanks road. The road had been made passable along its entire length for dog teams in 1907 and for light wagons in 1910. Also in 1910, a 90-mile spur was built from Willow Creek on the Valdez to Fairbanks road to Chitina on the Copper River and Northwestern Railway route. Territorial road-building begins After Alaska achieved territorial status in 1912, the Territorial Legislature repealed the 1904 road tax law and replaced it with a flat four dollar tax imposed on taxpayers no matter where they lived in Alaska. By this time, in 1913, the federally-operated Alaska Road Commission (ARC) had created 2,167 miles of trail, 617 miles of winter sled trail, and 862 miles of wagon road. 0f this mileage, the ARC considered the 419 miles of the Valdez to Fairbanks road its most important accomplishment. It was over this route, in 1913, that the ARC sent an army truck on an experimental journey. The truck completed a 922-mile round trip, including a side trip to Chitina, between July 28 and August 19, averaging about 50 miles per day. This was about double the mileage that could be covered in one day by a horse-drawn wagon or sled. Two years later, the legislature created road districts corresponding to judicial districts and provided for elected road commissioners to oversee each district. In 1917, this system was changed to provide for a Territorial Board of Road Commissioners and divisional boards in each district. The same legislature also appropriated $20,000 so that the territorial road commissioners could build shelter cabins along winter trails. The ARC continued to operate, so at this time there were two road-building organizations in Alaska: the federal ARC and the territorial road commission. During World War I, federal appropriations for road-building in Alaska decreased. But advances in road-building equipment and automobiles made during the war benefited Alaska after the war. Motor vehicles saved about one-third of the cost of horse-drawn traffic per ton carried per mile. The average cost of moving a ton of freight one mile was 37 cents by bobsled on a winter sled road, 50 cents by auto or truck, and $1.37 by wagon in summer. By 1919, automobiles and trucks made up about 90 per cent of the traffic moving over Alaskan wagon roads. In 1920, the ARC was able to acquire war-surplus army trucks and tractors, greatly improving its road-building and maintaining capabilities. In 1923, the Governor of Alaska reported that 1,517 people, 87 motor vehicles, 30 wagons, 24 double bobsleds, and 26 pack horses had traveled over the Valdez to Fairbanks route, which had been named the Richardson Highway in 1919. A total of 345 tons of freight, about one-third the capacity of a good-sized steamboat on one trip, had been carried over the highway during the year. The Department of Agriculture builds forest roads The Department of Agriculture, which managed large areas of Southeast and Southcentral Alaska as national forests, had its Bureau of Public Roads take over road and trail construction in the forests in 1922. Prior to this, the ARC had done road work in the forests under contract to the Department of Agriculture. As it relinquished the forest work, however, the ARC assumed a new responsibility. The territorial road commission was abolished and the ARC took over its work using territorial funds. Between 1920 and 1933, the budget of the Alaska Road Commission averaged about $500,000 per year. About 40 per cent of this came from taxes raised in the territory and 60 per cent from Congressional appropriations of money collected outside the territory. In 1932, the Alaska Road Commission was transferred from the War Department to the Department of the Interior. From 1905 to this time, the ARC had built 1,231 miles of roads, 74 miles of tram road, 1,495 miles of sled roads, 4,732 miles of trails, 329 miles of temporary flagged trails, 26 airfields, and 32 shelter cabins. The total cost had been over $18 million, nearly $12 million of which had come from the War Department. The Department of Interior takes over Alaska road-building With its new responsibility for road-building in Alaska, the Department of the Interior received authority to charge fees and tolls on Alaska roads. Until then, there had been no formal regulation on weight, types, or speeds of vehicles operated on Alaskan roads. Some Alaskans said this was/instigated by the Alaska Railroad, also operated by the Department of the Interior. Highway traffic had begun to compete with the rail route to Interior Alaska. In 1932, a bus company charged $10 for a one way trip from Valdez to Fairbanks while the railroad charged $47 for a one way trip from Seward to Fairbanks. In 1933, the Department of the Interior required all vehicles in Alaska to be registered and to pay license fees. Richardson Highway tolls were not charged for private vehicles, but commercial vehicles carrying 5 to 15 passengers had to pay a $100 to $175 toll. Cargo vehicles were charged by the pound, with rates varying from $100 for vehicles up to 7,000 pounds to $150 for vehicles between 7,000 and 10,000 pounds. Even with the tolls, improved automobiles and trucks had greatly reduced freight rates. Per ton costs were $6.30 for dog sled freight, $4.80 for pack train freight, $1.50 for wagon freight, and only 30 cents for truck freight. By 1936, the Alaska Road Commission was beginning to abandon mileage because of a decline in mining activity and because increased air service made some trail routes obsolete. In 1932, there had been 31 airplanes in Alaska and they had carried about 7,000 passengers 942,000 miles and about 500,000 pounds of mail and freight. Four years later, some 79 airplanes were in service in Alaska, carrying nearly 17,000 passengers over three million miles, over two million pounds of freight, and over 275,000 pounds of mail. The changing nature of transportation in Alaska caused the ARC to abandon its shelter cabins, maintained on winter trails since 1917, in 1941. World War II causes new highway construction in Alaska The Alaska Road Commission had built thousands of miles of trails throughout interior and Northern Alaska, and many short roads from communities to the nearest water transportation access. It had not-except for the Valdez to Fairbanks road-undertaken to link communities by overland routes. That came only with the military requirements of World War II. One of the first of those requirements was for a highway connecting air bases at Fairbanks and Anchorage. To make this connection, in 1941 the Alaska Road Commission began a road from the Richardson Highway, near today's Glennallen, to Anchorage. When completed, it would be possible for the first time to drive from Anchorage to Fairbanks using a portion of the Richardson Highway and the newly-named Glenn Highway. A highway from the rest of the United States through Canada to Alaska had been talked about as early as 1930. Congressional committees had recommended such a road in 1935 and 1939, but it was not until February of 1942, three months after the United States became an active participant in World War II, that a presidential committee recommended a highway link to supplement air and sea supply routes. Work on the new highway began at once from Dawson Creek, British Columbia, to Big Delta, Alaska. Seven U.S. Army engineer regiments and 47 civilian contracting companies finished the work in nine months and six days. The first "Fairbanks Freight" rolled up the highway in November of 1942. Work went on in 50-degree-below-zero weather as finished grading followed rough leveling. By December of 1943 the original bulldozed pioneer road had been upgraded to a permanent road 26 feet wide, gravel surfaced over 20 to 22 feet, with grades reduced to no more than 10 per cent and narrow bridges replaced by new two-lane structures. At the peak of construction in September of 1943 the Alaska Highway required over 1,100 pieces of heavy equipment. The total cost of the pioneer road exceeded $19 million. While the highway turned out not to be of much use in the military campaigns of World War II, for the first time people could travel to and from Alaska by other than sea or air. In 1944, the Alaska Road Commission assumed maintenance of the Alaska Highway between the Canadian border and Big Delta and also maintenance of the Tok to Slana spur of the highway. National defense needs upgrade Alaska roads World War II ended in 1945, but in 1947 the Secretary of Defense suggested that national defense required that the Alaska Highway, Richardson Highway, and Glenn Highway be upgraded to all-weather standards. The secretary also recommended completion of an Anchorage-to-Seward highway. As a result, in 1948 Congress passed a six-year Alaska road program to meet national defense needs. By this time the Alaska Road Commission had practically abandoned its old system of flagged winter trails, trails, and sled roads. The Denali Highway, linking Mt. McKinley National Park to the Richardson Highway, was begun in 1950. In 1951, the Glenn Highway had been upgraded except for a 16-mile unpaved stretch in the Sheep Mountain vicinity. Also in that year, ceremonies at Girdwood marked the opening of the Anchorage to Seward Highway. The following year it was possible to travel from the Alaska Highway at Tetlin over the newly-built Taylor Highway to Eagle. Much of this route followed the ofd 1899-1900 Valdez to Eagle military trail. In 1953, the Alaska Road Commission began construction of a Copper River Highway, planned to follow the old route of the Copper River and Northwestern Railway from Cordova to Chitina. By 1956, when the road commission's duties were transferred to the federal Bureau of Public Roads, it was maintaining a highway system of 1,000 miles of all-weather routes connecting the ice-free ports of Valdez, Seward, and Haines with principal cities and military installations and with the lower 48 states. A secondary road system connected this principal system with farming and mining communities. Isolated roads also gave remote communities access to air and water transportation. The transfer was significant because for the first time Alaska began to receive federal aid under the Federal Aid Highway Act. The State of Alaska takes over road-building When Alaska obtained statehood in 1959, the state became responsible for much of Alaska's road system. The new state took over 1,800 miles of connecting roads and 1,300 miles of isolated roads. The Copper River Highway was not completed, but by the 1970s the state had added to the system a new Fairbanks to Anchorage route, the George Parks Highway, built through the Nenana and Susitna river valleys. It had also, as a result of the 1964 Good Friday earthquake, had to reconstruct much of Southcentral Alaska's road system. To serve the developing oil fields on Alaska's arctic coast, the state built a road from Fairbanks to the Arctic Ocean in the 1970s. in the mid-1980s, the state was studying new roads across western Alaska to Nome, and along Southeast Alaska's coastline to link the capital city of Juneau with the road system.

|

|||||||||||||||||

|