|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Alaska's Heritage

CHAPTER 4-9: RIVER TRANSPORTATION

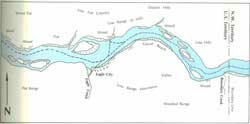

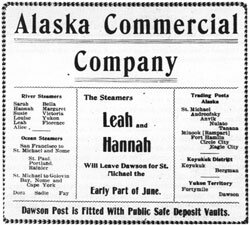

Americans introduce steamboats on Alaska's rivers The Americans who came to Alaska, like the Natives, Russians, and British who had preceded them, used the territory's rivers as transportation routes. Sometimes they merely used river valleys as corridors through the wilderness. When travel on the rivers themselves was possible, the Americans used the rivers' waters to float traditional Native craft, Russian baidaras, and an assortment of traditional American poling boats, rowboats, and sailboats. Americans also introduced steamboats to Alaska's rivers. Steamboats made a big difference to river travel in Alaska. The freight canoe or baidara could at most carry two tons on one trip. While travel downriver with the current was not too difficult, upriver travel required paddling, poling, or towing upriver by travelers walk-ing on the river banks and hauling on ropes. One trip a season was typical. Steamboats could haul several hundred tons of passengers and goods in one trip, depended on steam engines and paddles for their power, and could make several trips up and down river in one season. They had helped to open the western United States and to support a busy commerce between inland states and territories and the rest of the world. The first steamboat had traveled between Pittsburgh and New Orleans in 1812, and by 1860 hundreds of boats carried passengers and freight along the Mississippi River and its tributaries. By the 1850s, steamboats were also operating on rivers in the Pacific Northwest such as the Columbia and Willamette. In the latter years of their occupation of Alaska the Russians had used steam vessels in the coastal waters of Southeast Alaska and between Alaska and the Pacific Northwest, but they left introduction of steamboats on Alaska's rivers to the Americans. The Americans' first attempt to do so pre-dated their purchase of Russian interests in Alaska. When gold strikes on the headwaters of the Stikine River caused a stampede of gold seekers to that area, Captain William Moore took the steamer Flying Dutchman to the Stikine River in 1862. He made several trips upriver, carrying gold seekers and their supplies. A few years later, the Western Union Telegraph Expedition, which began construction of a world-circling telegraph line that was to run from North America across Asia to Europe, used the steamer Mumford to carry telegraph wire and construction material up the Stikine River. Another part of the same project, operating in northern Alaska, brought the small steamer lizzie Horner to Alaska with the idea of using the boat on the Yukon River. That did not happen because mechanical difficulties kept the Lizzie out of service. The expedition also brought another sternwheel steamboat, the Wilder, which was used in the coastal waters of Northwest Alaska. It was not long before smoke-belching steamboats, most of which thrashed the rivers' waters with paddlewheels, were used on many of Alaska's rivers. While these rivers ranged from Southeast Alaska's Stikine, Southcentral Alaska's Copper, and Southwest Alaska's Kuskokwim, most of the steamboats were used on the Yukon River and the smaller streams that flow into it. The Yukon goes up the Yukon River Two years after the United States purchased Alaska, the small stern-wheeler Yukon went into service on the Yukon River. The boat, 50 feet long and 11 feet wide, only needed 15 inches of water on which to operate. It began its first voyage upriver on July 4, 1869, pushing two open boats loaded with supplies and carrying a government surveying party. On this trip, the Yukon took 23 days of actual travel to go over 1,000 miles upriver to Fort Yukon. On the way, it stopped at Anvik on July 19 and Nulato on July 31 to establish trading posts. After its first voyage, launched with "flags flying and guns firing" according to one passenger, the Yukon settled into a routine carrying supplies to the company's trading posts on the Yukon River and taking freight and fur traders, miners, and prospectors up and down the river. One early traveler reported that the boat was so tiny that it "had to tow all the goods in barges...no cabin...stove was in the fire room and four could sit down to table at a time." Despite the Yukon's small size, it burned about a cord (a stack 8 feet long, 4 feet high, and 4 feet wide) of wood every two hours. The steamer, pushing one barge, usually took about 14 days to make the 901-mile trip upriver from St. Michael to a trading post called Tanana, located near the confluence of the Tanana and Yukon rivers. This first Yukon continued its trips up and down the Yukon River each year between May and September. Then in the spring of 1878, ice smashed the Yukon as it lay on the bank at Fort Yukon. The Alaska Commercial Company had already ordered a new, larger boat. This second Yukon was soon assembled and launched at St. Michael. The new boat was 75 feet long and 20 feet wide. Also in 1878, a trading company competing with the Alaska Commercial put the sternwheeler St. Michael in service on the Yukon River, but the Alaska Commercial Company soon acquired this boat. Then in 1882 a third steamboat began operating on the Yukon River. Edward L. Schieffelin led a prospecting party upriver in the New Racket. The New Racket reached Tanana before the 1882 freeze-up and Schefflin and his party spent the winter there. In the spring of 1883 they took the New Racket upriver to the Rampart area. Then this boat, too, was sold to the Alaska Commercial Company. Although the Alaska Commercial Company added the Arctic to its Yukon River steamboat fleet in 1889, the situation on the river did not change much until 1892. In that year the rival North American Trading and Transportation Company put the Portus B. Weare on the river. Built at St. Michael, the Weare was, with its 175-foot length and 28-foot width, the largest steamboat operating on the river. Its first season, the Weare went upriver to Nulato before being stopped by ice. The following year the Weare reached Fortymile. In 1895, the Alaska Commercial Company began operating the Alice and the Bella on the Yukon River. The North American Trading and Transportation Company added the john J, Healy to its river fleet. This year the Arctic made one trip from Anvik to Fortymile and four trips between St. Michael and Fortymile, a 14,000-mile record for one season. Klondike gold rush creates more demand for steamboats In 1897, only two ocean-going vessels unloaded passengers and freight at St. Michael to be carried up the Yukon River by steamboat to Interior Alaska and Canada. Five steamboats were serving Dawson and its vicinity, and not many more were operating on the lower Yukon River. After 1897, when word spread that gold was to be found on streams flowing into the upper Yukon River, there was a sudden demand for more steamboats to carry passengers and supplies on the Yukon River. By 1898, 30 new steamboat companies had been formed to compete with the Alaska Commercial Company and the North American' Trading and Transportation Company. Sixty new boats and barges were built to operate on the Yukon. The new boats could pay for themselves in just a single trip upriver, according to one estimate. One boat, the Leah, took 300 passengers and 600 tons of freight from St. Michael to Dawson. The Leah made a $41,000 profit on its first St. Michael to Dawson trip and profits of $131,000 per voyage on later trips, each one taking 20 days from St. Michael to Dawson and 10 days for the Dawson to St. Michael return. With returns like this possible, business people put as many boats as possible into operation on the river. Ten boats were built in a shipyard on Puget Sound and sent to Alaska under their own power. Remarkably, only one was lost on the way. The Alaska Commercial Company had four boats prefabricated at Jeffersonville, Indiana, on the Ohio River. They were shipped to Dutch Harbor and put together, then sent to St. Michael. Other steamboats were built at St. Michael and Whitehorse. In addition to the steamboats intended for commercial traffic, a few small boats were built by prospecting parties for their own use. These gold rush era boats accounted for many of the nearly 300 steamboats estimated to have been used on the Yukon River and its tributaries at one time or another.Life aboard the steamboats is much the same Although the Yukon River steamboats varied in size, life aboard ail was much the same. A typical boat had space for about 400 cubic feet of cargo. Such a boat, 1 75 to 200 feet in length and 30 to 40 feet wide, was powered by two to four boilers whose steam supplied power to two steam engines. At first wood, then coal, and finally oil fires heated boiler water so that it expanded into steam. Piped into the engines under pressure, the steam moved massive engine parts. The engines in turn moved long arms, called pitmans, back and forth. The pitmans, connected to each side of a paddlewheel at the stern of the boat, moved that wheel. Even the slowest wheel revolved 12 to 14 times a minute. Planks, called "buckets," running from one side of the wheel to the other, bit into the water and pushed it behind them, to move the boat forward. The sternwheels were almost equally efficient when worked in reverse. This was highly important in maneuvering in narrow river channels or rapid currents. A properly-built sternwheeler could, when reversed, "turn around on a dime and have nine cents change left over." The boat itself had two or three decks. The firebox, boilers, engines, and fuel-cords of firewood, coal in bunkers, or oil in tanks-occupied most of the first deck along with freight. Tall smokestacks rose from this main deck through the upper decks. From them issued clouds of smoke that signaled a boat's presence from miles away. The second, or "saloon," deck had an outer ring of small cabins that surrounded a long central cabin used as dining room and social area. The third, or "texas," deck had cabins for the crew. Either in front of the texas or atop it sat the pilothouse, from which the boat could be steered. There, a huge pilot wheel, often taller than the pilot and reaching below the floor of the pilot house, controlled giant rudders at the stern of the boat. More often than not, the steamboat pushed or had lashed to its sides one or more barges carrying additional passengers and freight. A vessel of this size might carry a crew consisting of the captain, one licensed pilot, as many Native pilots as possible-for the Athabaskans along the Yukon were sought out for their knowledge of the river's channels-a chief engineer, a second engineer, a first mate, a purser, a second mate, two fire tenders, two cooks, two waiters, two strikers, and a night guard. The navigating crew, divided into sections or watches, worked six hours on and had six hours off. Other crew members such as cabin help, cooks, and waiters followed an early-to-rise and early-to-bed routine. On the large boats, there was often room for officers' wives to accompany their husbands. Some, such as Captain John Fussell's wife, Agnes, who drew a chart of the Yukon River around Circle and Fort Yukon, contributed to operation of the boats. While underway, the deck crew was constantly passing wood to the fire tender. A two-boiler boat consumed about two cords of wood each hour, round-the-clock. Many boats had to stop every 10 to 12 hours to buy more wood at wood yards operated along the river by Natives or by disappointed prospectors. The boats also had to stop often to clean their boilers. The first such stop on an upriver trip came after the boats crossed from the shallow waters of the Bering Sea from St. Michael to the mouth of the Yukon River. The salt water put into the boilers on that section of the trip could cause the water in the boilers to foam and foaming water could injure the boilers. About 9 to 10 hours were lost as a boat stopped to put out its fires, allowed the boilers to cool, washed the boilers, and replaced the salt water with river water. Even then, the water problem was not solved because scale from the muddy river water built up `rapidly and the boilers had to be washed down again and again. On a typical trip, the boilers had to be washed once after entering the Yukon River and again at Anvik. On the lower Yukon, where the river was broad, flat, and had few obstructions, boats might go as fast as seven miles per hour upriver. Above the Tanana River, the Yukon became more treacherous and progress was slower.  Agnes Fussell's map of the Yukon River, a section of which is shown here, was a significant aid to navigation of the river. Collection Name: Anchorage Museum of History and Art. Steamboat boom ends as gold rush declines Heavy steamboat traffic continued up and down the Yukon River for just a few years. After the initial surge of activity when 98ers attempted to reach the Klondike, 99ers moved from the Klondike into Interior Alaska. As gold seekers moved from the Klondike and Interior Alaska to Nome in 1900, river traffic slowly declined. In 1901 the Alaska Commercial Company merged its river fleet with that of the Alaska Exploration Company and of the Empire Transportation Company to form the Northern Navigation Company. The Seattle-Yukon Transportation Company was later added to Northern Navigation by purchase. The Alaska Commercial Company retired its time-honored name and renewed its mercantile trade as the Northern Commercial Company.  This advertisement, which appeared in the Dawson Daily News on May 3, 1900, shows the extent of the Alaska Commercial Company's river operations. Collection Name: Alaska Historical Commission With its newly-bought boats, and linked to the river trade in Canada by its counterpart, the British-Yukon Navigation Company (another white Pass and Yukon Railway subsidiary), the American-Yukon Navigation Company expanded its Yukon River operations in 1914 to include runs between Dawson and St. Michael. Its boats also operated on the Tanana, Koyukuk, and Iditarod rivers. The rapidly expanding use of airplanes to carry freight and passengers to isolated villages previously accessible only by river travel, coupled with a decline in mining activity, began to cut into profits of the river traffic after World War I. In 1922, the American-Yukon Navigation Company closed its terminal at St. Michael and ended its service below Tanana on the Yukon River and on the Tanana River itself. The U.S. Army (which had been operating two steamboats to support its forts on the Yukon River) and small local boats replaced the steamers. The next year the Alaska Railroad, now completed from Seward to Fairbanks, took over the two army boats and began a riverboat service that lasted until 1954. The Alaska Railroad and the American-Yukon Navigation Company reached an agreement in the 1920s. American-Yukon Navigation would handle river traffic from Dawson to Tanana and go up the Tanana as far as the port of Nenana. The Alaska Railroad would operate boats from Nenana down the Yukon River to Holy Cross (later to Marshall) and up the Tanana River to Fairbanks. Small private boat companies, such as Day Navigation, serviced stops too small for the Alaska Railroad and American-Yukon Navigation Company boats to bother with, and also worked some of the Yukon's tributaries. Although a rise in the price of gold to $35 an ounce in 1933 and freight for military construction during World War II stimulated business along the river, in general American-Yukon Navigation and the Alaska Railroad lost rather than made money on their Yukon River steamboat operations. In 1943, American-Yukon Navigation sold five boats and all of its routes in Alaska to the Alaska Railroad. But the railroad lost over $150,000 a year on its river operations in 1946, 1947, and 1948. In 1950, the railroad boats stopped carrying passengers. In 1951, freight business had declined to just over 5,000 tons. In 1955, the railroad got out of the river business altogether. Some of the business persons who had been operating smaller boats on the Yukon River and its tributaries formed a partnership and bid on the railroad's river division. The successful firm began as B&R Tug and Barge, but soon formed Yutana Barge Lines. Modern, smaller boats and increased efficiency made the firm a success and by 1983, Yutana Barge Lines was virtually the only carrier operating on the Yukon River. Most freight and passengers reached river villages by air, and the riverboats' chief cargo was bulk petroleum.

|

|||||||||||||||||

|