Governing Alaska

The Alaska Railroad

The most expensive federal project during the territorial days was the Alaska Railroad, a project which by the late 1930s represented an investment of more than $10,000 per person for the 7,000 residents who lived in towns along the railroad.

It was the only rail line run by the federal government, with the exception of the Panama Canal railroad. In one sense the Alaska Railroad was an attack on the large, private shipping and transportation companies. It was also a response to the threat that certain business monopolies would control Alaska's future.The 1912 law that established Alaska as a territory also called for a railroad study, to help develop Alaska and its resources. In 1913 President Woodrow Wilson said a government-built railroad would be a key to unlocking Alaska's resources and opening its future.

Many in Congress were skeptical about whether the the federal government should build a railroad. But, as historian Edwin Fitch put it, "a faith in railroads combined with a lack of faith in railroad personalities," led Congress to swallow its doubts.

In early 1914, Wickersham delivered a five-and-a-half hour speech in Congress, advocating construction of a government rail line in Alaska. The approval of the railroad prompted celebrations in Alaska towns where residents imagined a new golden era. In Fairbanks, the Lipman Simson clothing store advertised that the railroad would allow quick shipments of the latest fashions from the East Coast: "It will not be so long now before we will be able to get this eight-day express service."

That quicker service became a reality nine years later when President Warren G. Harding traveled to Alaska to tap the $600 golden spike outside of Nenana. In time, the railroad also helped support large-scale gold mining in the Interior and rebuild the region after a decline during World War I.

After Harding reached Seattle, he predicted eventual statehood for part of Alaska. "Alaska is designed for ultimate statehood," he said. "In a very few years we can well set off the Panhandle and a large block of the connecting Southeastern part as a state. The region now contains easily 90 percent of the white population and of the developed resources...As to the remainder of the territory, I would leave the Alaskans of the future to decide."

Harding was a sick man as he spoke. He had fallen ill from food poisoning during his trip back from Alaska and he got worse as he rode a train south to San Francisco. He died August 2, 1923, apparently from a heart attack, less than three weeks after driving the golden spike in Alaska.

Not long after Harding's death, the Ketchikan Commercial Club responded to the former president's words by starting a secession movement, to make Southeast a separate territory. The supporters of what they were calling "South Alaska" held a vote that drew support throughout the region. Motivated by the belief that the rich fisheries of Southeast were supporting the territory, the movement's supporters said the rest of Alaska had a declining population and contributed only eight percent of the costs of running the government. The secession movement ended when a key Congressman declared that dividing Alaska in two for a total of 55,000 people would never win federal approval.

Federal Powers in Alaska

There was never just one government in Alaska during territorial days. In fact, the Secretary of the Interior under President Woodrow Wilson identified a "government of the forests, a government of the fisheries, one of the reindeer and Natives, another of the cables and telegraphs," and listed several more before he finished adding them up.

His comments reflected the reality that the real governing power in Alaska was not the weak territorial government, but was really the unelected officials from the nine federal agencies that had a hand in Alaska affairs. These various departments had as many as 38 bureaus operating in Alaska.

The federal agencies managed land that they controlled, often without taking any local concerns into consideration. This created ongoing controversy in Alaska, where the people thought their views should be given more weight.

Until statehood, 99% of the land was under federal control. Determined to avoid the mistakes of land use in the Western United States, a new conservationist ethic was applied to Alaska. It meant that federal agencies would retain control, instead of giving it to entrepreneurs. In 1906, President Teddy Roosevelt halted coal leases on public lands in Alaska, part of a long and complicated argument about whether one large company was trying to gain an unfair advantage and exploit a public resource.

This controversy increased the pressure for more rules about land managment. The idea was that the federal government should not give away its land, but try to manage it properly, and as efficiently as possible, inluding Mount McKinley National Park which was created in 1917. The Chugach National Forest had already been established in 1909 and the Tongass National Forest in 1905. The Tongass had been carved out of land occupied for generations by the Tlingit and Haida tribes. In 1935, Congress said that the Indians could file a lawsuit for payment for the taking of their land. The suit, filed in 1947 and settled in the 1960s, helped set important legal and political precedents for the Alaska Native land claims movement.

Salmon Politics

No issue got people in Alaska more excited than the dispute over fish traps. Even at the first territorial legislature, a law was debated asking Congress to ban the traps. For decades the fish trap had been a hated symbol of everything that was wrong in the territory. It was described in one anti-fish trap campaign as "Alaska's Enemy No. 1." Despite strong opposition to the traps from the public, the canned salmon industry and federal officials defended their use on the grounds that they were a labor-saving device and an efficient way to catch fish. The canned salmon industry generated up to three-quarters of territorial revenue in the years before World War II.

The typical fish trap was a series of large logs floating on the surface of the water along with a series of nets that salmon would swim through and be unable to escape from. The fish were stuck in place until the net was raised to collect them. The fish traps were cheap to operate and maintain, and they caught fish by the thousands.

Federal officials sided with the owners of the fish canneries who said the traps were vital to the industry. Alaskans viewed the fish trap not as a valuable labor-saving device, but as a contraption that unfairly eliminated fishing jobs by catching fish that would otherwise be caught by fishermen in boats. Fish traps were also blamed for damaging the fisheries and sending a fortune to the Outside owners of the canned salmon industry, instead of to Alaskans who wanted to earn a living as fishermen. The fish traps worked round-the-clock and could wipe out the salmon in an area.

A small number of large companies owned most of the traps, which became a symbol of Outside control of Alaska. One accounting in 1944 found that 396 of the 434 fish traps were in the hands of Outside firms.

In 1956, when Alaskans approved the proposed state constitution, they also adopted a law that banned fish traps by a margin of five-to-one. It took effect with statehood.

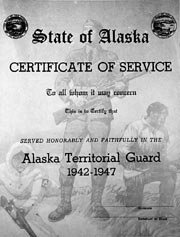

Alaska at War

For most of the 1930s Alaska's non-voting delegate to Congress, Anthony Dimond, argued without success that spending money to fortify Pearl Harbor in Hawaii without taking any precautions to defend Alaska was like locking one door of a house and leaving another wide open. He said the territory could be taken "almost overnight by a hostile force", and any effort to recapture Alaska would come at a cost of millions of dollars and thousands of lives.

A future five-star general and commander of the Army Air Forces in World War II Lt. Col. Henry H. "Hap" Arnold, became one of the most strongest supporters of the need to defend Alaska. It wasn't until the late 1930s that Congress finally acted, approving funds to defend Alaska.

Two years before the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the only military installation in the Alaska territory was the Chilkoot Barracks in Haines, an old Gold Rush facility where the troops had ancient Springfield rifles. Their only transportation was a 52-year-old tug boat with so little power that it couldn't move against a 30-knot headwind on Lynn Canal.The fortification of Alaska became an urgent national priority after the attack on Pearl Harbor on December7, 1941. People were afraid that Alaska would be used as a stepping stone to attack the mainland. From then on, military issues were a priority for the federal government.

The war brought the building of major military bases in Anchorage, Fairbanka and across the territory, along with many civilian airfields and other facilities. The building of the Alaska Highway along with other new roads and docks, wharves and facilities also contributed to the greatest period of sudden change in Alaska history. The government spent more than $1 billion in Alaska during World War II, a time that was both an economic and political turning point.Military and other government spending replaced fishing and mining as the major Alaska industries. From a high of 153,000 military personnel in 1943, the number dropped to less than 20,000 at the end of the war.

In the early 1950s, the government spent an average of $350 million per year on defense. In the 1940s, the civilian population climbed from 74,000 to 112,000. Because of the military, Anchorage became the economic capital of Alaska. The new immigrants joined with civic leaders from various towns in a campaign for political equality.

Links:

- President Roosevelt speaks at Adak in 1944

- President Roosevelt talks about the war and his trip to Alaska