|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Alaska's Heritage

CHAPTER 4-18: TOURISM

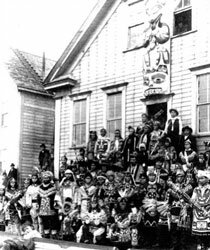

Alaska attracts tourists People world-wide traveled for pleasure or adventure long before Alaska was discovered. In the United States, publication of the journals kept by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark during their cross-continent expedition of 1803 enticed people to travel to the unsettled regions of North America. Beginning in mid-century, Alaska attracted travelers. More people became intrigued with Alaska during the 1880s when several individuals lectured or wrote books and articles about their travels in Alaska. John Muir, the foremost American nature writer of his time who first visited Alaska in 1879, was one who chipped away at Alaska's iceberg image. Muir and missionary S. Hall Young canoed through Glacier Bay. Upon his return to California, Muir wrote "To the lover of pure wildness Alaska is one of the most wonderful countries in the world." Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore, a 27-year-old woman from the Midwest, who visited Southeast Alaska in 1884, wrote a series of articles that appeared in newspapers and magazines nationwide. Later, the articles were published as a book and became the standard tourists' guide to Alaska for 20 years. Scidmore was invited to be a charter member of the National Geographic Society. A peak near Mount St. Elias was named Mount Ruhamah in her honor. Tours of Alaska become available  Tourists enjoyed watching Alaska Natives perform dances in traditional ceremonial dress. Pictured here are Chilkat Tlingits in 1904. Collection Name: Alaska Historical Library, Case and Draper Collection. Identifier: PCA 39-401 From San Francisco or Seattle the ships went to Victoria and Nanaimo, British Columbia. Their first stop in Alaska was Tongass or Loring or, after 1887, Metlakatla. Next they called at Wrangell, then perhaps another cannery, and then at the mining towns of Juneau and Douglas. At Douglas, the travelers had the opportunity to tour the Treadwell Mines. Some ships went to Glacier Bay. The last stop was Sitka where the visitors could see Baranov's Castle and the Russian Orthodox Church. At least once during the tour, the sight-seers had the opportunity to observe Natives performing traditional dances. Merchants quickly discovered that selling souvenirs was profitable. From his collection of photographs, Edward de Groff at Sitka offered prints for sale. When the ships arrived, Natives lined the waterfront and main streets to sell curios. The opportunity to see Native life and collect artifacts proved to be a powerful motivation to travel north. In 1884, there were 1,650 tourists who took the Inside Passage tour. Two years later the number of tourists increased to 2,753. In 1890, 5,007 travelers visited Alaska. Some steamship companies began to offer voyages to the Bering Sea advertising the chance to cross the Arctic Circle. To venture into the "land of the midnight sun" had great appeal to many people. Another appeal was to see animals in their wilderness environment. Still others wanted to see active volcanoes or glacial action.  Travelers aboard an Alaska Steamship Company ship. Collection Name: Alaska Historical Library, Skinner Collection Identifier: PCA 44-9-2 In 1899, E. H. Harriman, a railroad magnate, organized a scientific expedition to Alaska. He chartered a Pacific Coast Steamship Company steamer, the George W. Elder, and invited 25 scientists, writers, and artists, including John Muir, to accompany him and his family on a summer adventure that took them through Southeast and Southcentral Alaska, and into the Bering Sea, with a visit to Siberia. The results of the voyage were published in 14 books between 1902 and 1914. Writers lure more visitors to Alaska The Klondike and Alaska gold rushes lured a number of writers and poets to Alaska. Jack London wrote about the savage, frozen-hearted north. In The Call of the Wild, published in 1903, London drew on knowledge gained from spending the winter of 1897-1898 on the upper Yukon River. Robert Service came to the Canadian Yukon a few years after Jack London. Service's poetry describes the north as an "outcast land," or the "land God forgot." As the frontier vanished in the United States, it still existed in Alaska and northwestern Canada. National parks and monuments are created in Alaska Despite the early interest in mountain climbing in Alaska, the highest mountain in North America was not mapped or reported until the end of the nineteenth century. In 1896, prospector and adventurer William A. Dickey and several companions sighted the huge peak north of Cook Inlet. They named the peak McKinley because word of William McKinley's nomination for president by the Republican Party was the first news the men received when they emerged from the wilderness in the late summer. On February 26, 1917, the mountain and a large area surrounding it were designated a national park and big game reserve. Alaska's first national park was closely followed by the establishment of several others. At the recommendation of the first superintendent of Tongass National Forest, William Langille, national historical monuments at Sitka and Old Kasaan were created. Katmai National Monument, created in 1918, and Glacier Bay National Monument, created in 1925, were established for their scientific interest. Tourism begins to Interior Alaska When the Richardson Highway and Copper River and Northwestern Railway improved access to the interior of Alaska during the 1910s, groups in Cordova, Valdez, and Fairbanks promoted tourism. Visitors could view glaciers, mountains, and waterfalls. "The roadhouse cuisine is excellent, and fishing and hunting along the (Richardson) trail are good." The completion of the Alaska Railroad created new options for tourists of the 1920s and 1930s. The railroad organized and advertised the Golden Circle Tour. Tourists took a steamship cruise through the Inside Passage from Seattle to Juneau and Skagway. At Skagway they rode the narrow-gauge White Pass and Yukon Railway to Whitehorse. There tourists took a Yukon River sternwheeler to Dawson and on to Fairbanks. From Fairbanks the travelers rode the Alaska Railroad through Mount McKinley National Park to Seward. Steamships completed the circle to Seattle. The 4,000-mile trip took about 30 days. The trip cost $550. In comparison, a longer trip to Europe cost $350. Between 1929 and 1942 the Alaska Railroad operated a promotional office in Chicago. Once the railroad was built, Mount McKinley National Park was more accessible. Many people wanted to see North America's highest mountain. Until the 1940s, railroad passengers between Fairbanks and Seward had to overnight at the Curry Hotel that opened in 1923. The hotel was located 100 miles south of Mount McKinley Park. Its manager built a trail to a site from which to view Mount McKinley. The hotel also advertised a three-hole golf course, tennis court, and swimming pool. Shortly before the railroad eliminated the overnight stop at Curry, the National Park Service opened an 80-mile automobile road to Wonder lake, the best point to view Mount McKinley. The next year, 1939, the McKinley Park Hotel opened on the park's east boundary near the railroad. The number of tourists remains small In 1929, a total of 30,000 tourists visited Alaska. Fairbanks hotels could accommodate no more than 150 tourists at one time. At the most, 10 per cent of all Alaska tourists rode the Alaska Railroad. The Inside Passage tour was the most popular. The Alaska Steamship Company, one of the two major Alaska shipping operators, did not increase its summer passenger service through the Inside Passage from weekly to bi-weekly service until June, 1936. Alaska tourism booms after World War II After World War II, Alaska's tourist industry greatly expanded. The Alaska Highway, better known as the Alcan, beckoned many when it was opened to public traffic in 1948. The first year, 18,604 persons traveled the highway. As an aid to motorists, and also as promotion, The Milepost began annual publication in 1949. The publication was a guide to automobile service stations and rest stops and sights of interest along the road. By 1951, the number of travelers over the highway had increased to 49,564. Improvements in air service also made Alaska more accessible. The State of Alaska becomes involved with tourism Tourism became one of Alaska's most important industries. The new State of Alaska encouraged tourism when it began a ferry system from Prince Rupert, B. C. to Southeast Alaska ports in 1963. Later, state ferries linked Seward, Whittier, Valdez, and Cordova with Kodiak, Homer, and Seldovia in Southcentral Alaska. In Southeast Alaska the ferry system connected Seattle, Ketchikan, Wrangell, Petersburg, Sitka, Juneau, Haines, and Skagway. The ferries proved popular with tourists, and during the summer months reservations became necessary. The State of Alaska also created a Division of Tourism to promote Alaska. The agency worked with communities to provide and improve visitor attractions and with private enterprises that catered to visitors. In 1970, the State of Alaska established a Division of Parks to manage the second largest state park system in the United States and to deal with the growing interest in recreation and tourism. By 1975, tourism created around 7,500 jobs in Alaska. The State of Alaska realized about $15 billion in taxes and fees from the industry. Many people had come to regard Alaska as the last unspoiled wilderness. To those who viewed or those who ventured into the backcountry, the severity of wild Alaska was an attraction. At Mount McKinley National Park (now Denali National Park), backcountry use doubled and then tripled. A number of companies formed to offer backpacking excursions and river raft trips. During 1983 more than 650,000 people visited Alaska.

|

|||||||||||||||||

|