|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Alaska's Heritage

CHAPTER 4-15: MINING

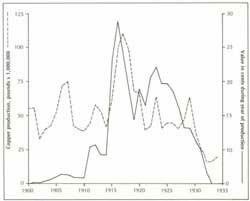

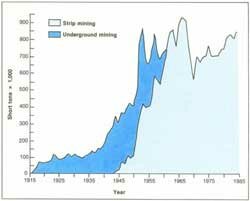

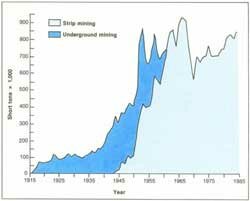

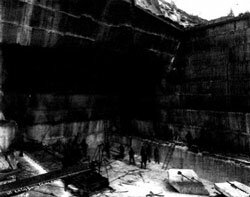

Alaska is rich on mineral resources Alaska, it seemed, was the scene of a continuing gold rush that started in the 1860s and extended into the early 1900s. Following discoveries in western British Columbia, gold was found in Southeast Alaska. Other discoveries followed. Prospectors found gold in the Fortymile River drainage and at Birch Creek in the upper Yukon River area. They found gold on the Kenai Peninsula in Southcentral Alaska. The world heard in 1897 of the Klondike gold fields in western Canada. Two years later, discoveries were made on the Seward Peninsula, more in Interior Alaska, in Western Alaska along the Innoko River and in the Kuskokwim River drainage, and in northern Alaska in the Chandalar River area. Gold seemed to be everywhere in Alaska. Alaska's mineral wealth was not just gold. Copper, coal, tin, platinum, mercury, and molybdenum were also found in Alaska. Most recently, Alaska's oil deposits attracted the world's attention. Prospectors fond gold in nearby Canada, then Southeast Alaska Inspired by the California gold discoveries in 1848, prospectors traveled north looking for gold. They followed the Pacific and Rocky mountains to Montana and Idaho territories and British Columbia. In 1861, Buck Choquette found placer gold about 160 miles above the mouth of the Stikine River. News of Choquette's strike spread rapidly among prospectors. Prospectors who headed for the Stikine River gold fields searched other parts of western Canada and into Alaska. In the summer of 1873, word spread of a new gold strike in Canada. Henry Thibert and a man known only as McCullough found gold in the Cassiar district north of the Stikine River. Gold was discovered a few miles from Sitka about the same time. A mining engineer, George Pilz, in charge of lode gold claims being developed near Sitka, encouraged area Tlingits to search for gold. Among those who brought samples to him was Chief Kowee of the Auk Tlingits. Kowee lived on the east side of Gastineau Channel, near what is today's Juneau. Pilz and Sitka merchant N.A. Fuller sent prospectors Richard Harris and Joseph Juneau to find the source of Kowee's sample. In October, 1880, Harris and Juneau found the area that Kowee had described. The two men made Alaska's first important gold strike. The discovery site was located several miles up Gold Creek. Harris and Juneau staked claims for themselves and their backers. News of the discovery brought a rush of prospectors to the area. A frontier mining town sprang up on the beach. It was first named Harrisburg, then Rockwell, and finally Juneau. Billy Meehan was one of a party of five who left Sitka On December 1, 1880, in a 25-foot canoe, bound for the new strike. On the way, the party camped near the southern end of Douglas Island on the west side of Gastineau Channel. On December 16, he found placer gold at the mouth of a stream later named Bullion Creek. By spring the "Ready Bullion Boys," as Meehan's party was nick-named, had recovered placer gold worth $1,200 from the stream gravels. In May, 1881, Pierre "French Pete" Erussard moved to Douglas Island and staked the Paris lode gold claim. He sold the claim later that year to John Treadwell. San Francisco investors had sent Treadwell to Alaska to scout the new strike. Ore samples were so promising that the investors organized the Alaska Mill and Mining Company. The company bought more claims on Douglas Island. In 1882, they moved in machinery for a five-stamp mill to crush rock and recover gold. Gold is found in Southcentral and Interior Alaska Although the Russian Peter Doroshin had panned gold in streams on the Kenai Peninsula, a noteworthy strike was not made in that area until 1888. That year, Charles Miller discovered gold on Resurrection Creek. After his discovery, prospectors staked claims along most creeks on the northern Kenai Peninsula. Two towns, Hope and Sunrise, became trade centers for the miners. When news of gold discoveries in the upper Yukon River region reached the Kenai Peninsula, however, most prospectors headed for the new fields. Prospectors also searched for gold along streams flowing into the Yukon River. On September 7, 1886, prospectors Howard Franklin, Howard Madison, and Mickey O'Brien found placer gold 25 miles above the mouth of the Fortymile River. The district's gold-bearing sands and gravels could be sifted only in the brief summers when water was available. It took large quantities of water to operate the sluice and rocker boxes that trapped the gold. Some miners tried to work year-round by keeping a fire going to thaw the frozen ground. They hauled buckets of dirt out of shafts to the surface and stockpiled the dirt until summer. Sluice mining was hard and profits were slim. Once in a while a Fortymile miner might recover as much as $200 in gold dust in one day. When Frank Bateau accumulated $3,000 in gold dust from the season's work in 1887, the others called him "King of the Fortymile." Gold recovery, although not in large amounts, was steady in the Fortymile region. Communities at Chicken, Franklin, Jack Wade, and Steele Creek grew as service and supply centers for area miners. A former prospector, Jack McQuesten, was working as a trader for the Alaska Commercial Company in 1895. He grubstaked Peter Pavlov, better known as Pitka, and his brother-in-law, Serge Cherosky. They found gold in the gravel of Birch Creek, another Yukon tributary. Almost overnight, Fortymile became a ghost town as prospectors rushed to Birch Creek. The town of Circle City was founded by the prospectors and camp followers. That winter 700 persons lived there. Klondike gold brings Alaska and western Canada to the world's attention The next year, 1896, Tagish Charlie, Skookum Jim, and George Carmack made their famous strike. In the spring, the three headed for the Tron-duick River, now called the Klondike River, in Canada. There, Bob Henderson, a Canadian prospector, had reportedly taken more than $700 in gold from a tributary. The discovery of gold on Bonanza Creek by the three men on August 17, 1896, brought Alaska and western Canada to the world's attention. When Joe Ladue, a trader along the Yukon River, learned of the strike he rafted supplies to where the Yukon and Klondike rivers meet. He staked a townsite named Dawson, in honor of George Dawson, head of the Canadian Geological and Natural History Survey. Word reached San Francisco and Seattle in the summer of 1897 of the gold strike on the Klondike River. The great gold rush of 1898 began. Ships raced up the Inside Passage carrying stampeders, horses, and mining equipment. Many Americans were among the thousands of fortune-hunters heading north. Some took the lengthy all-water route, traveling by ocean steamer to St. Michael on Alaska's western coast, then on riverboats up the Yukon River to the gold fields. The journey was possible only during the brief summer months when the waters were free of ice. Most stampeders chose an overland route. The best-known was the steep Chilkkoot Trail from a trading station, Dyea, at the head of Lynn Canal. There was also the White Pass Trail from Skagway. A less-publicized route was the Dalton Trail (earlier called the Chilkat Trail) from Haines. Others took the Stikine River trail to Telegraph Creek and overland to Teslin. One other route was the Valdez Glacier Trail, advertised as the "all-American route" to the gold fields of the upper Yukon. Over 4,000 people landed at Valdez to cross this trail in 1898. All of the routes were difficult. It was said that whichever route a person selected, he or she wished he or she had chosen another. One of Alaska's best-known villains arrived in the first wave of gold seekers. He was a confidence man named Jefferson Randolph "Soapy" Smith. Smith and his gang robbed or cheated many of the Klondike-bound miners who disembarked at Skagway. Smith was killed in a dramatic shoot-out during Skagway's heyday. When prospectors reached Dawson, they learned that most of the creeks had been staked by those who arrived the previous year. Only a few people found the wealth they were seeking.  Members of the infamous Soapy"" Smith gang who robbed and cheated many at Skagway." Collection Name: Alaska Historical Library, Case and Draper Collection. Identifier: PCA 39-843 Gold is discovered in Western Alaska David Libbey, while a member of the 1865 Western Union Telegraph Expedition, had found gold in the Niukluk River on the Seward Peninsula. Some 30 years later, he returned to that area to prospect. Libbey and his partners established the Eldorado Mining District and the town of Council City in 1897. They recovered $75,000 in gold before freeze-up. The following summer, three prospectors from Council City investigated reports of gold near Cape Nome on the Bering Sea coast. Storms forced their boat into the mouth of the Snake River, 30 miles short of their destination. Panning for gold there, the three men found gold an the sandbars. Continuing to search, they reached Anvil Creek where they panned large amounts of coarse gold. The "lucky Swedes," as the prospectors were nick-named, were John Brynteson, Jafet Lindeberg, and Erik Lindblom. After resupplying at Golovin, the three Swedes returned to Anvil Creek. There they formed the Cape Nome Mining District and staked 43 claims for themselves and 47 for their relatives and friends. Word of the Anvil Creek gold strike traveled along the Yukon River to Dawson during the winter of 1898-1899. Camps emptied as men and women rushed west to the new strike. When the news reached Seattle in the summer of 1899, more stampeders headed north. Nome was easier to reach than the gold fields of interior Alaska and Canada. Like those who had rushed to the Klondike, the prospectors from the west coast found the stream beds had already been staked. Troops from Fort St. Michael came to maintain order in the gold rush boom town of Nome. The beach sands at Nome are rich with gold One day a soldier at Nome went to get water near the mouth of the Snake River. He found gold in the beach sands. Frenzied digging on the Nome beach ensued. The commanding military officer enforced a land office ruling that claims could not be staked in the tidal zone, a 60-foot wide strip of beach. One Idaho prospector, John Hummel, went to work with a gold rocker and recovered $1,200 in gold in 20 days from the beach sands. During the summer of 1899, 2,000 men and women recovered $2 million in gold from the "golden sands" of Nome's beaches using pans, shovels, rockers, wheelbarrows, and buckets. When news of the beach gold and its easy recovery spread, many more people arrived at Nome. Advertisements led many people to think they could pick nuggets off the Nome beach with little or no work. At the height of the Nome gold rush, hundreds of tents extended for 15 miles along the beach to the west of town. In 1904 and 1905, old beach lines above tidewater were also found to contain gold. Other gold discoveries around Alaska follow Nome's gold fields had not been exhausted when a new stampede started. In a Tanana River valley creek near Chena Slough, Italian immigrant Felice Pedroni (Felix Pedro) discovered gold in 1902. By 1904 stampeders were on their way. A Texan named Robert Lee Hatcher located hard rock gold on a ridge below Skyscraper Mountain in the southern Talkeetna Mountains in September, 1906. Claims were quickly filed near what came to be called Hatcher Pass. Although putting lode mines into operation was expensive, three companies operated stamp mills in the district by 1912. The "golden trail" took prospectors around Alaska. During the 1900s, prospectors found gold along the Innoko River, a lower Yukon River tributary; along the Tuluksak River, a Kuskokwim River tributary; along the Chandalar River, in the Brooks Range; and along the Kantishna River, a Tanana River tributary. Large-scale mining operations take over After the initial strikes, mining companies organized to recover gold on a large scale. The operations were often financed by wealthy absentee owners. In a typical large-scale operation, a company would buy or lease a number of claims along a stream bed. The company would then bring in large machinery that could work ground that had been unprofitable for miners with gold pans and sluice boxes. Hydraulic mining, using pressurized hoses that could wash larger quantities of rock, was one large-scale method. Dredging, introduced in Alaska in 1912, was another. The dredges were boat-like structures that floated in artificially created ponds. They used continuous chains of steel buckets to scrape gravel from their ponds' bottoms. The gravel was then shaken through sluice boxes. By 1915, 21 dredges operated on gulches and streams of the Seward Peninsula. The U.S. Smelting, Refining and Mining Company and its subsidiary, the Fairbanks Exploration (F.E.) Company, began operations in Alaska during the 1910s and 1920s. The F. E. Company operated eight dredges in the Fairbanks area and employed nearly 500 people.  Large-scale mining operations replaced small-scale operations after the initial rush. This dredge on the Seward Peninsula had to be freighted to the site and assembled. It required a crew of at least eight people to operate and maintain it. Collection Name: Alaska Historical Library, B.B. Dobbs Collection. Identifier: PCA 12-60 Nearly as impressive as the Treadwell mines was the Alaska-Juneau mining complex on the other side of Gastineau Channel. Similar to the Treadwell mines, the Alaska-Juneau complex was a consolidation of numerous claims. By 1920, the Alaska-Juneau mine was the largest low-grade lode gold mine in the world. At its peak, the mill processed 12,000 tons of ore a day and employed 1,000 people. Between World Wars I and II, gold mining continued to provide jobs and profits. in 1923, the F. E. Company began construction of a 72-mile ditch system to carry water from the Chatanika River to its gold dredges and hydraulic equipment north of Fairbanks. When completed, the 12-foot wide ditch maintained a constant grade of 2.1 feet per mile and moved 81 million gallons of water per day. World War II curtails gold mining in Alaska In an attempt to stimulate the flagging economy in 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt increased the price of gold from $20.67 to $35.00 per ounce. The increase in price led to more gold mining in Alaska. This expansion continued until the early years of World War II when federal order E-208 shut down gold mines throughout the United States. Gold mining was not considered critical to the war effort. After the war, high prices and high labor costs, combined with the fixed price of gold at $35 an ounce, prevented most Alaska gold miners from resuming their operations. In 1967, the U.S. government could no longer support the world price of gold at $35 an ounce. President Lyndon B. Johnson freed the American dollar from its gold backing. Gold prices fluctuated dramatically in the late 1970s, at one time topping $500 per ounce. Claims in Alaska, many not worked for years, were again mined. Gold production in 1981 in Alaska was estimated at 125,000 ounces. Subsequently, the price of gold fell. Many mines shut down. In 1984, only a few continued to operate. One dredge operated near Nome. Other minerals attract attention to Alaska Prospectors also sought and found other minerals in Alaska. Deposits of copper, coal, silver, mercury, platinum, and tin were among the others found and mined in Alaska. The copper deposits in the Copper River basin had long been of interest. In 1899, an Ahtna chief, Nicolai, led prospectors to his own copper deposits. It had been a hard year and his people were hungry, so he traded knowledge of the deposits' location for a cache of food. The following summer, Clarence Warner and "Tarantula Jack" Smith were prospecting about 60 miles east of today's town of Chitina. On a sunny July day, the two men stopped to eat lunch. They noticed a bright green patch high in the mountain above them. At closer inspection, they found high-grade copper ore. The discovery, later the site of the Kennecott Mines, proved to be one of the richest deposits of copper ore ever located.  Copper produced from Alaska mines, 1900-1934. Collection Name: Alaska Division of Geological and Geophysical Survey, Division of Mining. The Kennecott copper mines are developed Copper mining began at Kennecott in 1911 after a railroad to haul the ore to a seaport had been constructed. The copper was mined from deep inside the Wrangell Mountains. A tramway carried the ore to a mill and concentrator. The concentrating process separated the ore into values (concentrates) and rejects (tails). The concentrated ore was further separated by smelting. Without coal, the copper could not be separated at Kennecott, so the concentrated ore had to be shipped to Tacoma, Washington. High shipping costs made it only profitable to mine high-grade ore. Local smelters using Alaska coal might have extended the life of some Alaskan copper mines. Political bickering, however, had killed such plans.  Coal production in Alaska, 1915-1984. Collection Name: Alaska Division of Geological and Geophysical Survey, Division of Mining. Alaska's coal fields are closed by political controversy Development of Alaska's coal fields, among the largest in the world, became entangled in national politics. The Natives, Russians, and early Americans in Alaska had used coal for their local needs. Many of Alaska's coal deposits had been discovered by 1900. Plans to mine and use some of the coal deposits were being made during the early 1900s. Among them were several proposals to build railroads in Alaska that would depend on easy access to coal to fuel their locomotives. Then President Theodore Roosevelt wanted the nation to conserve some of its natural resources for the benefit of all citizens. He feared that Alaska's coal resources would be used to benefit only a few corporations. He closed the Alaska coal fields to further entry. New claims could not be staked. Before Roosevelt closed the coal lands, almost a thousand claims had been filed in the Bering River coal fields near Katalla. The coal fields closure was the subject of much debate. Some said that eastern coal interests had engineered the closure because they wanted to prevent competition from Alaska coal. Other critics of the coal withdrawals blamed Gifford Pinchot, head of the national forest system, because new forest withdrawals in Southcentral Alaska included coal deposits. Local residents argued that coal imported to Alaska cost $15 per ton while the cost to mine local coal was $3 per ton. On May 3, 1911, a group of Cordova residents boarded a ship loaded with coal from outside Alaska and shoveled the coal into the harbor. Comparing their actions to the Boston Tea Party of 1773 where angry colonial citizens threw tea overboard to protest British taxes, local residents called the incident the Cordova Coal Party. The government, however, did not change its coal policies. When Pinchot toured the Bering River coal fields and Katalla oil fields in 1911, bitter residents tacked welcome signs that read "Closed-Result of Conservation" on the empty buildings in Katalla. The navy develops a coal field in Southcentral Alaska An 1898 army exploration party had located a vein of high quality coal that measured four feet across near the Chickaloon River. The deposits were difficult to reach and there was little interest in developing them unless a road or railroad was built through the area. During the winter of 1913-1914, the navy tested 800 tons of coal hauled from the Chickaloon River down the frozen Matanuska River and then to Seward. The tests showed that the coal had good burning properties and would be acceptable fuel for ships. Congress created the Chickaloon coal field reserve. When construction of the Alaska Railroad was approved in 1914, the plan included a spur line to the Chickaloon coal field. The navy contracted with the Alaska Engineering Commission to develop and oversee coal mining at Chickaloon. The first shipment of Chickaloon coal reached Anchorage in 1917. In 1919, more than 4,000 tons of coal were mined by Chickaloon's 35 employees. Two years later, the navy began building a million dollar coal washing plant at Sutton. The navy, however, was converting its ships from burning coal to burning oil. It closed the coal mine at Chickaloon and abandoned the partially-completed coal washing plant. Later, a few small local companies mined coal in the Matanuska River area. The coal was used by the Alaska Railroad and by people in nearby communities to heat their homes and businesses. Coal mining begins in Interior Alaska In 1918, coal mining began around Healy, a station along the Alaska Railroad in Interior Alaska. Four years later, Fairbanks business leader, Austin E. "Cap" Lathrop organized the Healy River Coal Company. In 1923, the Alaska Engineering Commission built a railroad spur line to Lathrop's mine near Suntrana. Coal mined in the Healy area was hauled by the railroad to Fairbanks. The F.E. Company used a great deal of the coal mined at Healy. Coal was also used to heat many of the offices and homes in Fairbanks.  Coal production in Alaska, 1915-1984. Collection Name: Alaska Division of Geological and Geophysical Survey, Division of Mining. Tin is mined on the Seward Peninsula On the Seward Peninsula north of Port Clarence, prospectors found gold and significant amounts of tin in 1899. The prospectors named the site York. It was the first placer tin deposit found in North America. The deposits were 90 per cent pure--as high in quality as the world-famous tin from Bolivia. Workers at the placer tin mine lived in a collection of shacks they named Tin City. Over the next decades, they extracted tin valued at more than $1.6 million. But because of high labor and shipping costs, operations were discontinued in the 1940s. Marble is mined in Southeast Alaska Early in the twentieth century, marble was quarried at Tokeen, located on an island off the west coast of Prince of Wales Island. Blocks of marble, some weighing as much as 11 tons were shipped to the Vermont Marble Company mill at Tacoma. There they were sawed and polished. Because of the high shipping cost, little polished marble returned to Alaska. At the peak of production, eight quarries in the area employed 70 workers. The quarries yielded more than $2.5 million in marble before operations ceased in 1927. Mercury is mined in the Kuskokwirn River watershed Although some gold deposits were found in the area the principal mineral wealth of the Kuskokwim River area was mercury. Commonly called quicksilver, mercury was used to extract gold from other minerals because it combined with gold to form an amalgam. Then the amalgam was heated to separate the mercury and gold. Mercury came from cinnabar ore. In the Kuskokwim River area whole bluffs were red with cinnabar. The Russians knew of the deposits near their trading post on the river. In 1906, W. W. Parks staked the Alice and Bessie claims near the village of Sleetmute in the central Kuskokwim River area. He began mining operations. Gold miners at Iditarod used mercury from Parks' claims. others staked mercury claims in the Sleetmute vicinity. Hans Halverson was one. in 1933 he staked a cinnabar claim he named Red Devil. Mines operated irregularly, responding to local demands for mercury. Most miners did not have sufficient capital to develop their claims.  Marble was mined from several quarries in Southeast Alaska during the early 1900's. Shipped to Washington for polishing, little of the marble returned to be used in Alaska. The pillars of the state capital building at Juneau, however, are of marble from Collection Name: Alaska Historical Library, Winter and Pond Collection. Identifier: PCA 87-433 Platinum is mined at Goodnews Bay In 1927, an Eskimo woman, Fanny Bavilla, told another Eskimo, Walter Smith, about "white gold" she noticed while trapping ground squirrels in the Goodnews Bay area. The white gold was platinum. Claims were staked and placer mining operations began shortly after. The Goodnews Bay Mining Company organized and purchased a number of placer platinum claims. In 1934, it began hydraulic operations and a few years later moved in a dredge. The Goodnews Bay mine was the only platinum mine operating in the U.S. After 1980, mining at the site was sporadic. High operating and labor costs and low prices paid for platinum cut into the company's profits. Recent mineral discoveries in Alaska are promising In 1974, U.S. Borax discovered deposits of an estimated 1.5 billion tons of molybdenum at Quartz Hill in Southeast Alaska. To transport the metal, the company began construction of an access road and dock facilities. Development of the deposits were to follow. Zinc and lead deposits found in Northwest Alaska also held promise of being profitably developed. Development of Alaska's oil and gas fields begins Alaska Natives, Russians, and early Americans had noted oil seepages in many locations around Alaska, but commercial oil development began in Southcentral Alaska when the first barrel was pumped from a Katalla well. The Alaska Development Company brought in the first gusher at Katalla in 1902, shortly after oil was discovered there. An old-timer named Tom White is said to have discovered oil at Katalla when he fell into a seepage pit during a bear hunt. White claimed that after he cleaned his gun and himself, he returned to the pit and threw in a match to see what would happen. The pool reportedly burst into flames and burned for a month. Numerous oil claims were staked in the Katalla and neighboring Yakataga districts east of the mouth of the Copper River. Others were staked in the Iniskin Bay district on the west side of Cook Inlet. Except locally, Katalla oil could not compete with fuel oil that was produced more cheaply in California. Also, like coal lands, Alaska oil lands were soon off-limits for exploration. In 1910, the federal government added oil land withdrawals to the coal land withdrawals. Production halted on all but one tract in the Katalla area that had been patented before 1910. Oil from the one tract was processed at a small refinery built in 1912. The oil had a high-grade paraffin base, and kerosene was a major product. The Katalla wells continued to operate until 1933. Then the refinery burned and was never rebuilt. During the years of operation over 154,000 barrels of oil were produced at Katalla. No successful wells had been drilled on Cook Inlet by the time of the 1910 withdrawals. Although exploration was renewed when an oil leasing law was passed after World War I, the Cook Inlet wells produced little but disappointment until later in the century. The government reserves oil fields in the arctic Many early travelers returned from the arctic and reported that they found oil pools there. A Hudson's Bay Company employee was one of the first. He noted seepages in the Canadian Arctic in the winter of 1837-1838. A member of Stoney's expedition brought back a small bottle of oil from the upper Colville River vicinity in 1885. When navy ships began to convert from coal to oil-fired boilers, the creation of oil reserves for possible war-time use followed. In 1912, two naval petroleum reserves were established in California. Three years later, a third reserve was defined in Wyoming. Then, in 1923, President Warren G. Harding created the 37,000-square mile Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 4. "PET-4," as it was known, stretched from Icy Cape to the mouth of the Colville River. After five years of study, the U.S. Geological Survey concluded that high quality oil was present there. The navy, however, displayed little interest in the reserve. Inexpensive fuel oil could be obtained from much more accessible sources. World War II renewed interest in petroleum reserves. By the fall of 1944, a naval exploration party, aided by a consulting firm, was in PET-4 to drill test wells. The first well in the reserve was drilled in 1945. In the 10 years that followed, navy contractors continued investigations and located two oil fields and a large gas field in the reserve. One gas field south of Barrow was developed to provide that community with fuel. Oil is discovered in the Swanson River area Interest in Southcentral Alaska's oil fields also resumed after World War II. New, more sophisticated methods of finding oil had been developed. Phillips Petroleum opened the first oil company office at Anchorage in 1954. Others followed. Seismic explorations led Richfield Oil Corporation to the Swanson River area of the Kenai Peninsula. On July 23, 1957, the company struck oil from an 11,170-foot test well on a tract called Swanson River Unit 1. Two refineries were built on the Kenai Peninsula following the 1957 discovery. Subsequently, seven oil fields and 13 gas fields were discovered off-shore in Cook Inlet. Cook Inlet oil and gas provided Alaskans with gasoline, diesel fuel, heating oil, jet fuel, and asphalt. A pipeline was built to carry natural gas from the Kenai Peninsula beneath Turnagain Arm to heat homes and businesses in Anchorage. The Prudhoe Bay oil field is discovered Several oil companies had leased land in the arctic from the new State of Alaska to explore for oil. In 1968, oil gushed from a well drilled by the Atlantic Richfield Company at Prudhoe Bay. The oil field the well tapped was estimated to contain 10 billion barrels of oil (a barrel holding 31 1/2-gallons). It was the largest oil field discovered in the United States, and the fourth largest oil field in the world.At the oil lease sale in 1969, the twenty-third since statehood, the State of Alaska invited bids to lease other North Slope land for oil exploration. The auction took place in Sydney Laurence Auditorium at Anchorage. Oil companies bid in excess of $900 million for state oil and gas leases on 179 tracts. Getting Prudhoe Bay oil to market proved to be a long process. The oil companies decided the best method of moving the oil was to build a 48-inch diameter, 789-mile long pipeline from the arctic to the ice-free port of Valdez on Prince William Sound. There the oil was to be loaded aboard tankers for transport to refineries in California. Billed as the largest construction project in American history and costing nearly $8 billion, the oil pipeline provided Alaskan newspapers with headlines for years. Congress approved construction of the pipeline in 1974. The line was built by Alyeska Pipeline Service Company, a cooperative venture of several oil corporations. The first oil flowed through the pipeline in June 1977. A new oil field near the Kuparuk River, 40 miles west of Prudhoe Bay, was discovered in 1979. Oil production began in 1981. This field contained an estimated four billion barrels of oil. In 1983, Alaska provided about 20 per cent of the total U.S. oil production. Over 1.7 million barrels of oil a day were produced. The same year, 180 new development wells were installed in the Prudhoe Bay and Kuparuk fields. Other oil exploration continued on the North Slope, in the Copper River basin, and in Cook Inlet. The North Slope also contained tens of trillions of cubic feet of natural gas, but this resource was not developed because of its distance from potential markets.

|

|||||||||||||||||

|